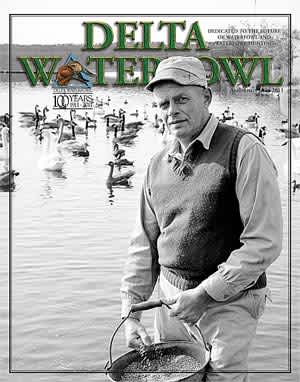

Al Hochbaum: How He Created the First Duck Research Facility

OutdoorHub 10.19.11

Bismarck, N.D.—When a young graduate student named Hans Albert Hochbaum set off to establish the first waterfowl research facility in 1938, no one could have guessed how wildly successful he would be.

During his 32 years as director of the Delta Waterfowl Research Station, Hochbaum created the most prestigious scientific research program on the continent and established himself as a passionate and articulate spokesman for ducks.

But if Hochbaum’s career has a fairy tale ending, the first dozen years were anything but. There was hardly a time when the station’s existence didn’t hang by a thread: During the 1940s Hochbaum twice quit his job, he feuded constantly with Ducks Unlimited and frustrated his sponsors at the American Wildlife Institute (AWI).

The story of those tumultuous early years is revealed in the current issue of Delta Waterfowl magazine, a commemorative 100-year anniversary edition based on old letters, manuscripts and station documents from a collection housed at the Archives of Manitoba.

The saga began in 1938 when General Mills founder James Ford Bell of Minneapolis, Minnesota offered his Delta Marsh hunting camp at the lower end of Lake Manitoba as a research facility. Aldo Leopold selected Albert Hochbaum, a brilliant and multi-talented graduate student from Cornell, to establish the program under the sponsorship of AWI.

Hochbaum was immediately enamored with the marsh, writing to Leopold a week later, “I can’t begin to tell you what a wonderful place this is. I would like to spend 10 years here.”

During those early years Hochbaum, fellow Leopold student Lyle Sowls and others unraveled the mysteries of the prairie breeding grounds one discovery at a time. They identified homing and re-nesting tendencies and territorial behavior, and examined botulism, predation, crippling loss and the impact of lead shot.

“It’s important to remember they were starting from ground zero,” says Dr. Frank Rohwer, Hochbaum’s 21st-century counterpart. “Everything they saw was new. Most of the research done to that point focused on the wintering grounds.”

Hochbaum lived by a simple credo: “Research is the search for the truth, and management is the application of truth,” and had little tolerance for anyone who didn’t play by those rules

“He was entirely principled and was not one to be put off by authority,” says Rohwer. “He didn’t back down from anyone.”

Hochbaum’s propensity to stand his ground when others were retreating manifested itself early and often. “I have strong personal convictions concerning the conduct of wildlife research and the application of its findings,” Hochbaum wrote to Bell in 1942.

Hochbaum’s first spat with DU was over the importance of the small, ephemeral wetlands he believed were the engine that drove prairie duck production.

DU, on the other hand, believed small wetlands were harmful to ducks because they often dried up leaving ducklings to die. DU had been founded in 1937 on the promise of “drought-proofing” the Canadian prairies by draining small wetlands into big, permanent ponds known as “kee waters.”

When AWI’s leadership told Hochbaum of its support for DU’s kee-waters approach, he turned to another former Leopold student, Art Hawkins of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for help. “Land that will produce a crop for agriculture should produce a crop of ducks even though some of the water…does not last through August,” he wrote, “but we must have the facts based on intimate study.”

Hawkins arranged for graduate student Chuck Evans to conduct research on the movement of broods, and Evans’ research confirmed what Hochbaum already knew: That hens move their broods to bigger water when small wetlands disappear.

Hochbaum believed DU was over-stating the duck population to exaggerate its accomplishments and secure liberal hunting seasons for its U.S. supporters, and complained bitterly to anyone who would listen.

The Fish and Wildlife Service shared his concerns, and in 1946 sent Hawkins and pilot Bob Smith to Canada to establish the annual spring breeding population and habitat survey, which during its 10-year development period was headquartered at the Delta Duck Station.

Officially launched in 1955, the survey became the largest wildlife inventory in the world.

In addition to recognizing the importance of small wetlands and being the driving force behind creation of the annual spring duck survey, Hochbaum also discovered a unique method of aging and sexing through cloacal examination.

Hochbaum is remembered by many for his gruff, uncompromising persona and his squabbles with DU; by others as a gifted researcher and relentless advocate for ducks.

“Al was a fabulous scientist,” says Dr. Rohwer, a former Delta student who enjoyed the hospitality of Hochbaum and his wife Joan on numerous occasions. “He was one of those really bright, gifted people. He could write well, was a great artist and a strong advocate for what he saw on the prairies.”

Hochbaum retired in 1970 to concentrate on his writing and painting. He continued to fight for small wetlands until his death in 1988.

For more information about Delta Waterfowl and its 100-year anniversary: www.deltawaterfowl.org/100years/.