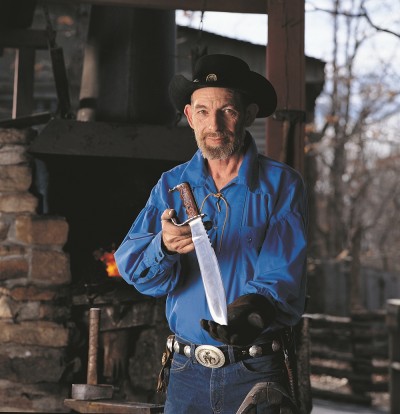

Keeping a Bladesmithing Tradition Alive in Southern Missouri

Marty Basch 05.17.13

His knives are found throughout the world, from a hunter’s hand following success in the woods to a coveted collector’s case in a country far away.

“I am a steel and tool maker,” says 73-year-old Ray Johnson in a deep Missouri drawl. “Basically sixty percent of my money comes from knives that haven’t cut anything but a collector’s finger. I am a tool maker first. If it happens to look good you’ve got a bonus.”

Johnson’s domain isn’t in a small Main Street shop in the rolling Ozarks of Branson, Missouri. Where he plies his craft is a bit unusual. He’s in a homey neighborhood that oozes 1880s life, sharing the path with a leather maker, chip carver, and blacksmith all a short walk from the rousing Outlaw Run, a new $10 million double-barrel rolling wooden roller coaster with a 16-story drop.

He’s part of a colony of heritage craftsmen, some 100 strong, that also includes glassblowers, potters, and candlemakers.

Though he’s been working with steel for more than a half-century, Johnson creates his knives ranging in price from a few hundred dollars to about $5,000 in Silver Dollar City, a Branson amusement park.

He’s been there since the late 1980s grinding and polishing the Mountain Outfitter knives before affixing the guards and handles.

Johnson’s something of a local legend. He went straight from high school into the welding world where where he worked for over 25 years before becoming the known knife maker. But there’s more to the loquacious Johnson. He’s a poet too often molding together his savory words while working on his latest knife or manning the counter in the shop.

As he often says in the poem “A Bladesmith’s Prayer,” “I know we’ll be eaten’ fruit from the tree of life, but how’re we gonna peel it if we haven’t got a knife?”

That’s a valid point and Johnson’s knives are popular with collectors from Japan to Russia.

“They buy hoping that upon my demise they will go substantially up in value,” he says. “I can’t guarantee that but it’s like the stock market or anything else. Wise collecting of knives int the past thirty years have paid more than a CD. But it’s like the stock market or anything else. You’ve got to know who is who.”

He’s known for making knives of Damascus steel, some with 640 layers of steel, often taking between 40 and 100 hours to make. Some are one-of-a-kind. He also uses motorcycle chains, chainsaw chains, and carbon steel.

But the knives he’s most keen on are the blades that get used.

“The ones I’m most proud of are the working blades, the ones that go out every day and works,” he says. Like the one he always carries with him. He takes it from a belt side carrying case.

“I have carried that old knife since 1980,” he says. “It is one of my early Damascus. It’s been through one elk. I don’t know how many whitetail. I have used and worn off about a quarter inch over the years.”

Though hunters and anglers use his knives, he’s quick to point out other uses, like the 400 blades he says went to U.S. soldiers in Iraq.

“Now they don’t fight with knives,” he says. “They probably dig in the sand with them, break boards off of buildings, and break windows out. I build a tool to do that with.”

Nearly seven days a week, 12-14 hours a day, Johnson says he’s working. He’s also brought in a fellow knife maker to tutor.

Johnson knows he’s anachronistic. He calls himself a dinosaur and laments a throwaway society versus a time when a knife maker’s tool was used for work in daily life.

“I usually tell people that when they buy one, it’s not the last knife you’ll ever buy, it’s the last knife you’ll ever need.”