Pike Prove Elusive in Sweden’s Famed Archipelago

Patrick Durkin 06.11.13

I don’t know if your life can flash before your eyes in the milliseconds before death, but I know your imagination can fillet, skin, and cook a northern pike in the nanoseconds before a landing net can engulf it.

That’s why I blamed myself and swung a fist in frustration when the pike shook my hook, pumped its tail and torpedoed to freedom in the brackish waters off Alviken, Sweden. It wasn’t the largest pike I’ve ever lost, but it would have weighed about seven pounds, or 3.2 kilograms. That’s enough to provide dinner for me, my wife Penny, our daughter Leah, and Tom Heberlein and Betty Thomson in their loft apartment in Stockholm.

That’s assuming, of course, that I’d have persuaded our fishing guide, Patrik Lindström, to let me keep it. And that we’d find a plastic bag large enough to carry it on the train back to Stockholm 35 miles, or 58 kilometers, to the north.

All those wishful plans escaped with the fish. “That’s what I get for thinking what I’d do with a fish before I actually caught it,” I told Lindström.

Well, no matter. We’d had fun the previous four hours fishing among the islands of the Stockholm archipelago on the Baltic Sea, which spans several tens of miles up and down the coast from the Scandinavian country’s capital. We caught a few pike earlier, but released them with little thought. Why? They were smaller pike, about 24 inches, or 61 centimeters; and Lindström said he preferred to release pike, not eat them–just as most Americans release bass and muskies.

If we had been catching zander, the European walleye, or salmon, we might have skipped comparing our catch-and-release beliefs. As it was, Leah, Heberlein, and I had plenty of questions for Lindström as he guided us May 30 on Sweden’s coastal waters.

For instance, how do freshwater fish like pike and zander survive in saltwater? Answer: Sweden’s many freshwater rivers dilute the Baltic’s saltwater just enough along the coastline to let these fish adapt and prosper.

The Stockholm archipelago is world renown for big pike, and Lindström said 20-pounders aren’t unusual. Well, actually, he said 10-kilo pike aren’t unusual. I keep making these metric references for Heberlein’s amusement. He and Betty have spent six months or more each of the past 10-plus years working in Stockholm, and so they slip casually into metric-speak.

In contrast, Lindström and I are two fishermen divided more by measurements of weight, length, and temperatures than countries. Each time we asked each other about the pike’s preferred spawning temperatures–or our countries’ average, heaviest, or longest pike–our conversational gears started grinding. Heberlein rescued us each time with the conversions, acting as clutch and flywheel to keep our discussions moving.

Lindström and I found it easier to discuss lure colors, lunar influences on fishing, and the whens and wheres of pike activity. We agreed red, yellow, and orange are good colors for cloudy days and dark or stained waters; and silvers and blues are good for clear waters on bright days.

We also agreed it’s fun to track moon phases and lunar-based predictions for fish activity, but found them too unreliable to dictate when we fish. The only reliable way to catch fish is to fish hard and fish often. Therefore, we decreed “fish are still fish” whether you chase them in Sweden or Wisconsin.

We further agreed weather and weather patterns largely dictate success. We settled that minutes after Lindström, a Stockholm resident, met us that morning outside our hotel near Heberlein’s place, and loaded us into his pickup truck for the hour-long drive to his boat.

“Everything is late this year,” Lindström said. “Usually the pike are in the shallows by now, spawning and feeding on baitfish. It’s been so cold the baitfish aren’t in yet. Some days the fishing’s not so good.”

Ha! Like guides everywhere, Lindström was keeping our expectations in check. As it turned out, he was wise to do so. Even though he and his clients caught many pike the previous day, he knew it meant nothing today. When it was our turn, we had to cover lots of water and make scores of casts for each pike that struck our heavy crank-baits.

Never were we bored, however. Lindström knew the waters well, and each spot reminded us of places we’d fished in northern Wisconsin or northwestern Ontario. He also pointed out relics of Sweden’s Cold War history with the former Soviet Union.

As we passed over deep troughs between some islands, he noted where Sweden once stretched anti-submarine nets. When passing over shallows between other islands, he pointed out submerged logs, pilings, and concrete barriers that once kept warships from passing.

And when nearing Sweden’s former Musko Naval Base, he pointed to a dotted red line on his sonar/GPS unit: “If we had stopped where we are now a few years ago, we’d see a patrol boat and face questioning,” he said.

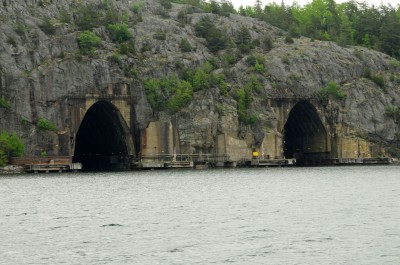

Much of the Musko facility has since been sold or shut down, but the most impressive part remains: three long tunnels cut deep into the granite island that once provided bombproof drydocks and docking facilities for Sweden’s warships and submarines.

This underground naval base took from 1950 to 1969 to build, and required blasting and hauling away 1.5 million tons of rock to carve out its tunnels and 12-mile (20-kilometer) underground road system. The facility remains connected to the mainland by a two-mile (three-kilometer) road tunnel that dives 230 feet (70 meters) beneath sea level.

When it was time to quit fishing, we reluctantly performed our “just one more cast” rituals and returned to Nynäshamn. From there we walked to a nearby station to catch a train to Stockholm.

Now that’s something I’d never done before: consult a train schedule to return home from fishing. Even better, our Stockholm transportation passes–purchased a day earlier for its bus, subway and trains–covered our fare. Talk about convenience. That’s like fishing Lake Michigan from Milwaukee and catching the 3:20 train to Waukesha. If there were such things.

“I could get used to this,” I told Heberlein as we sped along without worrying about construction delays or road rage. “Next time, I might splurge and go for the whole day or chase salmon in the Baltic Sea.”

I’ll just remember to wait until the fish is in the net before planning dinner.