The Duck Blind Blues

Josh Wolfe 09.19.13

When the words, “Take ‘em,” reached my ears, I wrapped my hand around the cold, black steel of my Benelli shotgun and commenced to shooting. Like any duck hunter who enjoys eating duck, I gave the group of green-winged teal everything in the pipe. When the smoke cleared, one duck lay dead on the water, one flew a half-mile and then sailed down into a rice field, and the others acted as if they might give us another chance. What harm was it to them? Four hunters in the blind shooting three times each at six ducks and emitting hundreds of tiny pellets that would surely hit something didn’t seem to give us very good odds.

We had pulled into camp the night before. To me, we are practically there when we beat the throngs of Memphis traffic and finally cross the I-55 bridge over the muddy Mississippi River. Off I-40 at the Brinkley exit and down to Wal-Mart for provisions and liquids to prevent life-threatening illnesses we go. After our wallets bump their heads on hunting licenses (not to mention state and federal duck stamps), a couple of 30-packs of Busch beer (the ones with the camouflage cans, of course), and tungsten Black Cloud shells (which are like buying toilet paper with Vitamin E and aloe as opposed to single-ply), we hop back in the truck for the final leg to duck camp and a temporary release from the real world. When we get into camp and into the house, piles of delectable treats and full whiskey bottles arranged three deep line the bar. There is nothing real about this. It’s Christmas for married men who work all week to play on the few lucky weekends they are given kitchen passes. In their world and in this one, I’m just a guest.

As a guest, I perform my duties without being told. Somebody needs a beer? I’m on it. Hell, there are 59 more where that came from, buddy. What was your name again?

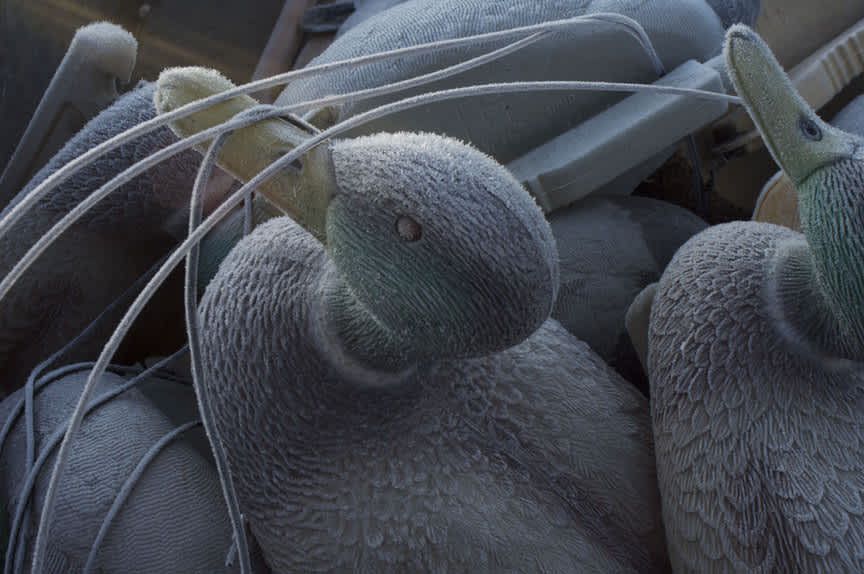

I unload the truck by myself, taking my host’s and my clothes into the house and into the room we will be sharing. I place his bag by the set of bunks near the door and mine near the far wall. I have slept in close proximity with this particular host many times and know the sounds he makes in his sleep. I also take the liberty of fixing myself up with an extra blanket, mainly for noise reduction reasons. I then go back out into the cold for our duck gear. I haul waders, shells, shell bags, guns in waterproof cases, Muck boots, band-laden call lanyards (this is promising), decoys (motorized and traditional), and the cooler into the “mud room.”

Except this “mud room” is spotless. Everybody’s gear is compiled into a neat section, each pile separated from the next by an immaculately clean floor. I set our stuff against a bare spot on the wall and stack and restack everything until it sits as flawless as an untouched Jenga set. With a broom, I sweep my tracks as I leave the room, marveling again at the neatness and starting to feel resentment towards these men and what a “mud room” is supposed to be. These men are not long from the depths of their wives’ employ; I give it two days before their teeth grow and their coats become thick once again.

After planning the next morning’s hunt, who would go where, watching a raunchy comedy back-to-back, and dealing with the loss of both 30-packs, we break for bed with high hopes and spinning heads. I just shut my eyes when I hear an alarm, then another and another. They all go quiet simultaneously until another breaks the silence. When that one decides to snooze, I roll over for another nine minutes until the grand finale of bells, robot voices, and ducks quacking light up the house like a fire alarm in the Pentagon. Time to go duck hunting.

I jump out of bed and get dressed with the enthusiasm that only a hunter who had arrived in camp the night before could have. The lights were on in the kitchen and coffee was already brewing. I passed a sluggish soul who hardly looked at me when I smiled and said, “Good morning!” Now that I think about it, he’d gotten real liberal with the camouflaged cans of Busch beer. Serves him right.

In the kitchen, I pour myself a cup of coffee and dilute it with Bailey’s. I step outside to look for the colors of the pending sunrise in the east, but there are only stars. We are duck hunting, right? Isn’t this is the one where we roll out of bed 30 minutes before shooting light and get to the blind with minutes to kill? Or did I somehow dream about duck hunting when I am really in deer camp? I suddenly feel delirious. Back inside the clock on the coffee pot reads 3:30 a.m. Nobody seems to be awake anymore and I begin to feel as if I’m watching myself on TV. Who is that strange character and what is he doing? What is he thinking? Doesn’t he know he lives on a planet inhabited by ducks that you can’t shoot until a regulated shooting time, which won’t be for another three hours? I notice a copy of Playboy on the coffee table and open it to see what I feel. Nothing. I find an old article that is actually not an article, but an expense report by Hunter S. Thompson, and dive in. I’ve really lost it.

Just then I hear a door slam. The other hunters slowly emerge from their warm beds and malodorous bedrooms where abstract noises were made throughout the night. Life is real! I meet them in the kitchen to go over the plan again even though I recited every detail until I fell asleep. I would be going to a blind with Stacy, whom I’ve hunted with a few times, Bill, whom I’ve also hunted with a few times and the guy who would eventually say, “Take ‘em,” and Wayne, my host. For now, they seem to resent my uppity attitude and respond with grunts and nods while sipping their coffees. These hunters apparently know something I do not. Wayne even seems to lack my vigor and leans against the counter having a one-on-one with his coffee cup. Apparently the duck report was bad or somebody’s dog had died last night. I could not tell which. This went on for another half-hour until, individually, we started outside to the “mud room.”

Still knowing my place, even though I was ready to go even if that meant carrying everybody’s gear, I wait and go in the “mud room” last to put on my waders. The last time I’d duck hunted was in Arkansas the year before. For those of you who know about the Arkansas mud, or have heard Hank Williams, Jr. sing about it, you know that mud is unlike mud anywhere else in the country. It is a gummy, residue-like substance that can serve as an adhesive if necessary. Arkansas mud gladly pulls feet out of wader boots causing falls, the loss of shells (sometimes a gun), and in many cases, the end of the day’s hunt. It is unforgiving and is not forgiven.

There are a few things that I don’t believe in doing due to the necessity and benefits of simply not doing them. For instance, I don’t make up my bed, knowing that the chances of me sleeping in it again that night are pretty good. My feelings on waders are the same. Waders are rugged, durable creations that don’t require a wash after each use though many duck hunters seem to think they do. After I use my waders, I hang them to dry and that’s that. They stay in the mud room at my house and sometimes visit other mud rooms where their muddy peers receive them with an unadulterated graciousness.

As I slowly slip my waders on and dry mud begins to redecorate the floor, I feel perspiration emerging from my pores. I pray nobody walks through the door while I’m making a mess. I ease over towards the broom and dustpan when I’m done and sweep myself out of the room. Outside, I feel fine knowing I narrowly escaped a scolding by one of the fellows who has been trained and set in his ways by a member of the opposite sex. As the cool wind dries my sweaty brow, I realize my gun and shells are still inside.

In the blind we sit and wait for shooting light that is almost an hour away. When we’ve all had a chance at telling a joke, it’s time to check the decoys again and do some readjusting. More bamboo is added to the already over-camouflaged blind. Luckily for me, there are machetes hanging on the back of the blind. If I were an underworked employee at NASA, I would spend my downtime looking for duck blinds like this one via satellite. When the decoys are readjusted and the blind rebuilt, we settled in to wait…again.

In duck hunting, there are two ways to determine shooting time. The first, and more conventional and legal way, is to wait until the specified time on the little timetable they give you at Wal-Mart. The little card can be folded in half and slipped into a wallet right along with your hunting license, state duck stamp, federal duck stamp, and proof of American citizenship. The second way, and the way I’ve always believed made it righteous, is to load up and get ready after another group within earshot has given their first volley of shots. The Game Warden will completely understand if you justify your reasoning by saying, “Well, they did it first.” In the distance we hear the unmistakable reports and get ready.

The four of us stand at the front of the blind, watching for whistling silhouettes to cross the grapefruit-colored sky. I stare so hard that I begin to see spots. A pair of wood ducks buzz our blind and then are gone. In the dark I had loaded my shotgun without being able to see the shells. I’d paid hard-earned dollars, too many of them in fact, for Black Cloud tungsten shells, the next best thing to lead—if not better. I missed the good old days of shooting ducks with high brass lead shells that would knock a plane out of the sky if it was flying too low. I was approximately 12 years old when the law changed and lead was outlawed. The good old days…

After the lone teal is retrieved and the other is given up for the coyotes, I notice something bewildering at my feet. The three empty hulls are not Black Could tungsten three-inch shells, but Fiocchi steel 2-3/4-inch shells! Quietly panicking, I open my blind bag where there are no Black Clouds. I keep my composure. Somebody, either in this blind or the other, has my shells. I suddenly want there to be no ducks killed this morning. If the Game Warden does show up I’d be the best prepared to tell him why we started shooting before the legal time. Even though it is not my party, I’ll cry if I want to.

I slowly look around the others’ feet, not wanting to draw attention to myself. Stacy, who is beside me to my left, is shooting bright red Remington steel. He is left-handed so where his hulls lay, there is no denying they aren’t his. Bill, at the far end of the blind to my right, is too far for me to see. Bill is a serious duck hunter; surely he is not the culprit. Wayne is the closest person to my right. He is shooting a Beretta Onyx. Knowing the spent hulls from an over-and-under would be behind him rather than beside, I take a step back and look down. Bingo!

“You think you hit one of those ducks?” I ask in the friendliest tone I could conjure up without sounding fake.

“When I shot, that teal hit the water,” said Bill without taking his eyes off the sky. Thanks, Bill. Time for a new direction.

“He hit the water dead, didn’t he? What kind of shells are you shooting, Bill?”

“Black Clouds. That tungsten stuff really hits ‘em hard,” he replied, still looking at the sky. The sun was just about to break the horizon and the stars had almost all retreated until the next night.

I look at Wayne, aiming my mouth towards his ear so he’ll know I’m speaking to him. I reach into the pit of my stomach for an authoritative voice and begin to launch my words when Bill cuts me off. “’Preciate you bringing those.”

“Huh?”

“The shells. Your dad said you bought them for us to try out.”

I look at Wayne, my face turning red in the dying darkness.

“Dad!” I start to explain that these shells don’t just magically appear at my front door step. I work overtime just so I can pay $4 per shell that will kill ducks better than lead.

He, too, never takes his eyes off the sky as he begins to speak, “It’s like this, son. I spent years when you were a little boy, wiping your butt and changing your diapers. Your mother made me forego many hunting trips to take you to baseball and soccer games. I’ve always told you that when I get old, you’re going to be the one wiping my butt and let’s say tying my boots because I’ll be damned if I ever wear diapers again. Plus, your shells must have gotten mixed up with all the stuff in the mud room.”

All he said resonated with truth except the last part. As I begin to laugh, two more wood ducks buzz our blind. Men who use bad toilet paper are more susceptible to grumpiness from the damage it causes to areas worthy of mentioning, though I won’t. Men who shoot poorly are more apt to blame it on the gun or ammo rather than the gun’s operator. When toilet paper is used, it goes down the drain. Shells are shot and that’s the end of it. A can of beer gets drank and then the can gets recycled or thrown in the fire depending on your whereabouts. You see where I’m going.

Shells are just material objects no matter the punch they pack. They cover blind floors, dove fields, and skeet courses, and stake claim to various pieces of earth around the world until they decompose or are picked up. I am lucky to be a pupil of so many wise elders. Like many things my father has taught me, it was his action that stood tallest. Somehow, by the end of the hunt, I was thanking him for shooting my shells without asking.