Alien Invaders: Non-native Species in the United States

James Swan 09.20.13

Non-native wildlife and plant species like quagga mussels, sea lampreys, alewives, nutria, Burmese pythons, brown tree snakes, mitten crabs, ruffe, purple loosestrife, water hyacinths, piranhas, alligators, and so on are among us. Some wreak havoc on ecosystems, and some can be a blessing.

Sometimes non-native species arrive by accident. Quagga and zebra mussels hitchhiked into the Great Lakes in the bilge of ships. Some come as pets that are freed and then take root, like mynah birds, parrots, and red-eared slider turtles. Others just get out of control, such as Asian carp, which were introduced to Mississippi to clean algae out of sewage treatment ponds before a flood enabled them to escape into natural waterways. Since then they have taken hold in many areas of the Mississippi River system and are poised to enter the Great Lakes.

People may also smuggle non-native species for profit. The international illegal trade in wildlife is estimated to be second only to drugs in value. California game wardens tell me that drug dealers, for example, have a liking for pet tigers, lions, and wolves. One Northern California USDA animal damage control trapper told me that has caught 75 “wolves” in response to livestock depredation complaints over the last decade in California’s “Green Triangle,” where marijuana is the biggest cash crop. There are no native wolves in this area. Apparently growers like to raise the animals to guard their crops. It is sometimes possible to buy “100 percent purebred” wolves online—which are illegal.

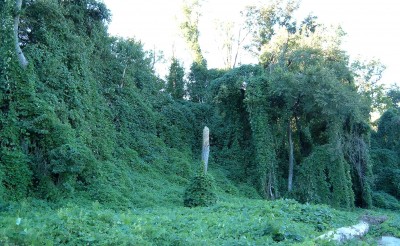

Other times the best of intentions go wrong. Brown trout are fun to catch and tasty, but they also can gobble up native species like golden trout. Kudzu vine may control erosion, but in the process it will swarm over everything else. Pigeons may be colorful in a park, but at best they are good food for owls, hawks, and falcons. Starlings were brought in because they were Shakespeare’s works. English sparrows were supposed to help control insect pests. They have become the most abundant bird species in the world.

Salt Cedar or tamarisk was imported into this country to control erosion, but in arid areas the plant consumes large volumes of water, resulting in drought. Water hyacinths from South America were imported as decorative plants for ponds in people’s yards. Then they got out and now completely take over aquatic ecosystems, smothering native plants. You get the idea.

Bricks and niches

Think of an ecosystem as a wall built of bricks. The bricks at the bottom support all those above. The space for each brick in that ecosystem is called a “niche.” The ones at the bottom are the plants. Then come the critters that eat plants, and finally critters that eat critters sit on the top.

Natural systems like to use all the available niches, but sometimes an empty niche crops up. Nature has mechanisms to fill empty niches. We have trout living in high mountain lakes because fish eggs stick to the feathers of aquatic birds that fly from lake to lake. Aquatic birds were the first stocking program, long before state agencies and planes dumped fingerlings into mountain lakes.

Animals and plants can compete for niches. Nature is not choosy. Sometimes those competitions are natural, as when wolves and mountain lions battle to be the apex predator in an area. Other times they are the product of human actions—accidental or on purpose.

When sea lampreys got into the Great Lakes through the Welland Canal, they feasted on lake trout and whitefish and those native populations crashed, creating an empty niche of top-level aquatic predators. Then alewives got into the Great Lakes and multiplied in huge numbers without anything to eat them, resulting in beaches covered with piles of stinky, small, and oily fish.

A lampricide was developed to control the Great Lakes’ lamprey population, but the job of top aquatic predator was open, and there was a glut of food. In the 1960s the Michigan Department of Natural Resources had the bright idea to introduce Pacific salmon into the Great Lakes. It was a brave move that worked. Today salmon are now found throughout the Great Lakes and the lake trout, steelhead, and whitefish populations are coming back. They have more salmon in Lake Michigan than we have in the Sacramento River these days.

Chukar partridge, Himalayan snowcock, and ring-neck pheasants are other good examples of introducing a foreign species into an empty niche and having things work out well for ecosystems and humans.

Introducing Atlantic coast striped bass and shad into California waters has worked, but you have to be careful when you tinker with nature because ecosystem balance develops over a long time. Some folks want to declare stripers “exotics” and eliminate them from California waters to help king salmon runs increase.

Every non-native introduction comes with risk. Northern pike may be native to Canada and the Great Lakes region, but if you drop them into a California lake like Lake Davis, the trophy trout population virtually disappears. Should those pike escape into the Sacramento River ecosystem, things could turn out very poorly. It’s bad enough that we already have native squawfish in the system that gobble up young trout and salmon like McDonald’s french fries.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife spent millions trying to eradicate pike from Lake Davis, fish that people in Minnesota would love to catch. No one knows how they got there yet; theories spawn freely in those parts.

Culture and regulations

Cultural attitudes can play a large role in introducing non-native species. The best fish for eating is always fresh fish, but in Asia, diners take it a bit further. Many Asian cultures consider fresher food to contain more life force energy, or “chi.” And abundant chi is good for your health. Some also consider food to be comparable to medicine. On a lecture tour to Japan, I recall a memorable dinner where there was a pool of fresh saltwater about 25 feet in diameter in the center of the restaurant. Swimming in the pool were live fish. Diners sat around the edges of the pool. When you wanted to order fish, you pointed to the one you wanted. The waiter then caught it with a net, and the cook cleaned and prepared it as you watched.

The northern snakehead fish is an example of another species that is valued in Asia, and despised in the U.S. These guys will eat almost anything and can crawl out of water and slither along to nearby ponds and rivers, engulfing anything in their path.

California is inundated with over 1,700 foreign species of plants and animals that compete with native species, and sometimes carry diseases. According to the University of California-Riverside Center for Invasive Species, every 60 days California gains a new and potentially damaging invasive species. Six of those species get established every year, resulting in economic losses to the state estimated at $3 billion per year.

You can be fined up to $50,000, get a year in jail, or pay damages for introducing a new species of plant or animal without a permit.

California has a whole host of regulations to control invasive species, but still, lots of non-native species keep showing up—like bullfrogs.

Bullfrogs and leopard frogs were first introduced to California a century ago when native frog species were depleted. Since then bullfrogs and leopard frogs have taken over most of the state, putting pressure on the native red-legged and yellow-legged frogs, which are on the endangered species list.

California has been allowing importation of bullfrogs—more than two million a year, most are raised commercially in Taiwan—which go primarily to Asian markets and restaurants. The law says that they must be killed before leaving the market or restaurant, but you know how that can go. Snapping turtles, red-ear sliders, western painted turtles, and Texas spiny soft-shell turtles also are not native to California, but they also are imported for food in the Asian community. According to UC Davis Herpetology Professor Bradley Shaffer, when non-native turtles escape, they “out-compete, out-reproduce, and eventually out-number native species.” Turtles are also can carry salmonella and parasites.

On April 8, 2010, the California Fish and Game Commission passed regulations forbidding importing live non-native frogs and turtles, as they “pose threats not only to the State’s native turtles and frogs, but to the native source populations of the imported turtles and frogs […] including disease, hybridization, competition, and predation.” The law pertains only to frogs and turtles to be used for food.

California is not alone in such regulations. Oregon has a law that states that “No person may import, purchase, sell, barter or exchange, or offer to import purchase, sell, barter or exchange live bullfrogs. Individual bullfrogs may be collected from the wild and held indoors in an escape profs aquarium. Release is prohibited unless the person first obtains a permit from the Director.”

In these days of intercontinental travel and cultural diversity, plant and animal species will spread, whether we like it or not, but we can help control their spread. Sportsmen have a responsibility to be aware of what they may be transporting, whether it’s bait, your catch, hitchhikers on trailers and boats like quagga mussels, or purposefully bringing your favorite fish or a pet turtle into a new area and releasing it where it’s not native.

As you travel from place to place, please be mindful to not bring along any non-native species as bait or hitchhiking on your boat or boat trailer. An excellent guide to cleaning vessels of invasive mussels is available here (pdf).

If you should see someone who is illegally transporting non-native species, you can report them to that state’s resources agency or Canadian province’s poaching-polluting hotlines. Not only will you be helping protect the environment, you will get a reward if your tip leads to an arrest.