The BAREBOW! Chronicles: Two Monsters with One Arrow

Dennis Dunn 12.02.15

During the winter of 2003 and 2004, I managed to get things figured out pretty well. If I were ever going to graduate from the Murphy School of Hard Knocks, I would simply have to assassinate the Headmaster. By the time I flew into Unalakleet on May 15, 2004, I was starting to feel quite hopeful once again. Almost confident, in fact, though I couldn’t explain why.

That spring there were to be two other veteran bowhunters in camp with me. Jake Ensign and Bob Miller were both determined to take a male grizzly with their bows. Neither, as I recall, had hunted Ursus arctos (horribilis) before, but our collective bowhunting experience, together with our passion for the intense challenge, quickly created a bond between the three of us.

It was a great relief to learn from Virgil and Eric Umphenour that this year our hunting would not be disturbed by the spring commercial herring fishery that had begun to affect so adversely the bear activity along the coast toward the end of my previous year’s hunt. All kinds and sizes of boats had swarmed up and down that part of the Norton Sound coastline, aided and abetted by noisy, spotting helicopters hovering over schools of herring along the water’s edge, and as the hunt wore on the bears seemed to arrive from the interior a little later each night, and depart a bit earlier each morning.

In this connection, there is a rather remarkable story I’d like to share now with the reader that unfolded the very last night of my spring hunt in 2003. It would have been too tame, too anti-climactic to append it to the end of the previous story, but it will serve as an amusing and instructive prologue to the night of May 18, 2004, which was to become my “night of nights,” and the pinnacle experience in this one person’s lifetime of bowhunting.

On a virtually windless evening, Eric and I set out from camp around 10 p.m. and headed the outboard in a southwesterly direction, well out from the shore. We kept the engine running slow and quiet, and (while we proceeded down the coast) we carefully glassed every foot of “beach,” as well as the tundra behind. At the stroke of midnight, the sun slipped below the horizon, leaving us to wonder when we were going to see our first bruin for the outing. In the distance, a half-an-hour earlier, I had picked up through my binos a long, white object lying right on the edge of the water. My eventual guess, as we slowly narrowed the gap, was that we were looking at a rare, beached (or dead) beluga whale. Though it had not been there 24 hours earlier, it did, indeed, prove to be a beluga (quite dead).

Approaching the whale, still yet a half-mile distant, we noticed a very blonde sow with two cubs starting to come down off the bluffs above the carcass. These were the first bears we had seen all evening, so we decided that staking out the whale-site till daybreak was probably as good a strategy as any. The sun had set only minutes earlier, but as soon as she caught sight of our boat on the calm water, the mama bear headed for the top of the bluffs as fast as she could get there—cubs in tow, right behind her.

At least their quick departure enabled us to go quietly ashore, anchor the boat on the back side of a little rocky point, and take up a vigil inside a nifty niche at the bottom of the cliff, no more than 50 yards from the beached whale. The rocky contours at that location would allow me a further approach to within 20 yards, without my being visible to any bears that might decide they wanted to add whale blubber to their diet.

Some native passing by earlier had stopped to cut out a long strip of blubber from one flank. The excision had produced a very noticeable oil slick which stretched several hundred yards out to sea, carried along by the nightly offshore breeze. “Oil on troubled waters” came to mind as I contemplated with awe the reflected afterglow of the recent sunset. The surface of the long, serpentine slick was even calmer than the ocean surfaces on either margin. The effect was rather eerie.

It was nearly 1:30 a.m. when the sow and cubs reappeared at the top of the bluff and came down again to the edge of the ocean. The mother signaled her cubs to stay put at about 30 yards away from the gleaming white carcass while she checked things out to make sure it was safe for the little ones to come on in. Her solo investigation produced one of the most humorous scenes I have ever witnessed in the wilderness. Since the Beluga was resting on its back, the soft underbelly was facing skyward. Our sow proceeded to mount the head and then walk gingerly the 16-foot length of the carcass. Reaching the tail, she turned around and started back toward the rib cage. Upon arriving at mid-abdomen, the bear decided she really liked the spongy, bouncy feeling she was experiencing, so all of a sudden she began jumping straight up and down—as if she were on a trampoline! Eric and I thought we were going to die laughing.

The gymnastic exhibition continued for perhaps 20 seconds until it was suddenly interrupted by the sow herself. All her antennae were abruptly focused out to sea and down the coast—directed toward some threatening menace she could evidently hear, but which we could not. Her cubs were still waiting patiently for the all-clear signal when their mother bolted past them in a second mad-dash for the top of the bluffs. As she paused on the skyline to take one last “listen,” we finally could hear the distant whine of the outboard motor that had first alerted her to possible danger. Through our binoculars, we soon picked out the small boat that was making the racket. The driver, no doubt, was seeking to take advantage of the calm night to make his first spring trip from St. Michael to Unalakleet—a distance of some 65 miles across open water.

The sow was obviously not taking any chances. Long before anyone in the boat could have spotted our trio of bears, they were long-gone and nowhere to be seen. My guide and I agreed that what we had just witnessed provided much food for thought. Unfortunately, no other grizzly deigned to put in an appearance the rest of the night, so after the sun had been up again for about an hour we headed back to camp—to pack up and head home.

***

They say persistence pays off, and 2004 finally proved to me the truth of that old saw. When I arrived in hunting camp on May 15, it was my seventh attempt to take a grizzly in the space of just three-and-a-half years. I had hunted grizzly bear before in both British Columbia and the Yukon Territory, but my 2003 spring hunt had convinced me that Alaska would eventually reward my perseverance if I simply hung in there and refused to give up.

The truth of the matter was that I couldn’t wait to return to that same stretch of coastline for one more attempt on the life of Mr. Griz. In all candor, my wife and mother weren’t too thrilled (to put it mildly) about my going back again, but I was convinced my luck was about to turn. On the morning of May 14, I boarded a plane for Fairbanks, and by the afternoon of the next day I was settling into the same comfortable tent camp out of which I had hunted one year earlier.

In Alaska, the regulations allow you to hunt 24/7 during any open season, so once again Eric and I had to adjust our sleeping schedule in order to take full advantage of the nocturnal activity of the big bears. On Monday evening, May 17, Virgil Umphenour and his camp cook, Paul Johnson, treated the three of us bowhunters to a terrific, steak-and-baked-potato barbecue. Since we had just awakened fresh from a long day’s sleep, this was absolutely the best breakfast any of us had ever had!

At about 10 p.m., Eric made up a sack-lunch and readied our boat for the night’s hunt while Jake and Bob prepared to depart with their own guides for very different sections of the coastline. Winds were low, spirits were high, and the waters looked friendly. Whenever the winds there raise enough to produce major ocean swells or wave-action, it becomes very dangerous to put ashore, and to get the boat anchored safely. Since we were blessed with a calm evening, however, conditions were nearly ideal for glassing without having to fight the pitching motion of the boat. Fortunately, I had the presence of mind to ask Paul, our camp cook, to accompany Eric and I. I don’t know if I actually had an intuition that this was to be my night, but I know I was hoping that any close encounter could be captured on video this time—unlike those in the spring of the year before. When bowhunting the big bears of the North, the critical moments of truth almost never get filmed, unless a third person is there in the hunting party. If things turn ugly at such close range, they happen so fast the guide simply doesn’t have time to put down a camera and pick up a rifle.

On the way down the coast, Eric and I saw a couple of sows, each with two cubs—but no single bears. Just after midnight, we put ashore on the end of a rocky point that projected well out into the ocean, and which gave us a view of several miles of shoreline in both directions. Eric had just finished setting up the spotting scope on his tripod when Paul announced he had spotted (through his binos) a large, heavily built boar coming up the coast toward us about two-and-a-half-miles away. We all found him in our optics within seconds and watched in fascination as he fished his way along the edge of the water, scavenging for herring. Between us and him, we soon spotted four other grizzlies working the shoreline: a mother with a pair of cubs and a loner we judged to be probably an average-sized male.

Not knowing just how long the big boar might remain out in the open before seeking cover inland, we went to meet him as fast as we could manage to move along the rocky shore. Before long we saw the smaller boar pick up the scent of the larger one and take off for the interior like a scalded cat. A few minutes later, the drama repeated itself with the sow and her young litter. By the time we had covered about a mile on foot, our quarry had closed to within 400 yards, and I realized I needed to choose a good ambush spot in a hurry. My choice was a five-foot-high boulder right on the water’s edge. In fact, it formed the very tip of a little boulder pile that stuck out into the ocean 10 or 15 yards, and it really did provide an ideal place for an ambuscade. The slight, steady breeze, such as it was, blew off the “beach,” into my face, and out over Norton Sound. As I settled in for the final wait, I was standing in a foot of seawater; the gentle waves lapped quietly around the calves of my neoprene boots.

Eric and Paul picked a smaller pile of rocks in which to hunker down, roughly 15 yards behind me as I stood facing the approaching beast. Soon he was less than 100 yards away, and I realized then that this truly was a beast of a big boar! The slow ponderosity of his methodical gait, moving from one boulder to the next, seemed to convey a sense of utter dominance over everything in his ken. A sense of royalty, perhaps. A veritable King of the Tundra, and of the Seacoast as well. Did I really have a chance to outsmart this old monarch? If so, I was going to have to outsmart Murphy, too.

Suddenly, with the bear at no more than 60 yards, and just as I was starting to feel that at long last I might actually get the best of my invisible enemy, I felt his icy breath on the back of my neck once more. I watched in horror as my quarry turned away from the water’s edge, walked slowly up to the brush-line above the beach, and disappeared from view! This was no fickle breeze taunting the hackles of my neck! This was Murphy’s ghost getting his jollies yet again at my expense, and I could hardly believe my eyes! Had my luck turned sour at the last moment one more time? Did the bear possess some sixth or seventh sense that told him danger was close at hand? I knew he could not possibly have gotten our scent! Over my many years of bear hunting, I had had many different bruins do the same sort of thing to me—for no discernible reasons. At times, their senses are altogether uncanny.

I guess I’ll always wonder what it was that quickly turned that grizzly around and brought him back to the water’s edge, and then into my waiting arms. Maybe the creature simply had to go “potty” and preferred the privacy of the bushes to the open, rocky shoreline. (I seriously doubt that.) Maybe Murphy’s ghost had at last taken pity on me after one final prank. In any case, when Brutus lowered his huge head to negotiate his footing up onto the big flat rock next to the one I was hiding behind, I came to full draw, and the die were cast.

I still had to wait about 10 seconds, however, until he gave me the broadside opportunity I wanted. For a moment or two, with his head raised and his body facing straight toward me, I felt tempted to fulfill his obvious death-wish by releasing the arrow right into the middle of his chest. Yet I knew the wind was in my favor, and I had counted on the weak, early-morning light to combine with his relatively poor eyesight to prevent him from picking up the slight motion of the top limb of my bow as I drew. That was the only thing I could think of that might give away my presence. Knowing the upper limb would be silhouetted against the still-bright western sky, that was precisely why I had waited to draw until the monster’s head dropped down to help him make that final ascent into my lair. I also knew that, unless he wanted to go swimming in deep water, he would eventually have to turn broadside in order to pass inland of me. So I waited.

As things turned out, the old boy was clueless, and I didn’t have to wait long. On Tuesday morning, May 18, at 1:25 a.m., in the half-light of the arctic spring night, I released my three-blade Savora broadhead at his rib cage from just eight yards away. Once on its journey, my arrow first skewered Murphy’s ghost, then passed through both the bruin’s lungs, exited the far side, and sailed another 25 yards beyond, to land among the beach boulders of the Bering Seacoast. The moment of truth had come and gone. It was all over save the shouting.

I’ve been asked many times since then, if—during the grizzly’s final approach—I wasn’t shaking in my boots, with my heart pounding in my throat. The reader may think it odd, but the answer is no. I was so totally focused on what I had to do, there was simply no room for fear in the picture. Besides, if a hunter allows fear to get even a foot in the door, he is much more likely to make errors of judgment or timing that could very well lead to lethal consequences for either himself or his guide—or both.

I hope the reader will not conclude that I’m being naive here. In the previous seven years or so, I had read every book I could find on the subject of bear attacks against man. I know how quickly they can kill you—or virtually any other living thing. I know that, with one swing of a powerful forearm, they can send a man’s head spinning 30 yards through the air like a soccer ball. As you will read in future chapters from The BAREBOW! Chronicles, I’ve been charged twice by an Alaskan brown bear (kissing cousin of the grizzly). I’m certain there are many people who simply don’t have the right temperament for bear hunting. Those that do, however, learn quickly that stern self-discipline and dispassionate rationality are essential to maintaining a laser-like focus in the field, and thereby to minimizing your risk of harm.

My arrow had knocked the wind out of my bear on the pass-through, and the video shows that he stumbled slightly in the first few seconds of his flight for cover. I’m guessing the brute didn’t last more than about 60 seconds. Eric, Paul, and I did not actually have the satisfaction of seeing him go down, but four hours later—when it became light enough at last to distinguish the stains of red against the nearly black rocks of the beach—we began the blood-trailing and quickly found him 175 yards away. He was lying on his back in a willow creek-bottom. Rigor mortis was in evidence, big time! Persistence and determination had finally paid off and yielded a dividend, the richness of which I still didn’t realize until a few hours later when the skinning of the head had been completed.

To this day, I’m still in shock and awe, and substantial disbelief: that my old monarch of a griz—with almost no sound teeth left in his mouth—turned out to be the new archery World’s Record! Three of his four canine teeth were completely missing, long since broken off at the gum line and rotted away from there. The empty nerve canal holes were showing on several severely-worn teeth. I’ve little doubt he was staring at least a $300,000 dental bill in the face! It was his time to go. When Alaska Fish and Game eventually completed their tooth study, he was found to have been 28 years old. Fifteen years is considered quite old for any bear. Twenty-eight is almost unheard-of—especially for a male, since they do so much fighting throughout their lifetime. Although his spring coat was in excellent condition, his hide was scarred in many places, and we found at least five old, leathery, healed-up bullet wounds on his back and rump. He had clearly had a number of other close encounters during his extraordinarily long lifetime. It was the kind of circumstantial evidence that injects into a hunter’s heart an extra dose of humility and gratitude.

The hide squared out at a bit over eight feet (which isn’t all that huge for the species), but the skull turned out to be immense, and that’s the only criterion used for entry into the various record books. After the mandatory 60-day drying period, the skull was officially measured at 26 and 5/16 inches. That remains its permanent score in the All-Time Boone and Crockett Records, and at the time of this writing—amongst nearly 700 entries, most taken with a rifle—it still ranks in the top three dozen ever taken. It turned out to be the largest grizzly bear taken anywhere in North America with any weapon in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008.

After being re-measured in April of 2005 at the site of the Springfield, Missouri biennial Pope and Young Convention, Old Snaggletooth was officially declared the new archery World’s Record at a final score of 26 and 3/16. The old record of 25 and 13/16 had been taken in 1987, and tied again 10 years later.

Unlike big game animals whose horns and antlers can be viewed externally and evaluated analytically through high-powered modern optics, bear and cougar skulls are encased inside many layers of muscle, fat, hide, and fur that make accurate field-judging almost impossible. I’ll be the first to admit that I was just amazingly lucky to be at the right place, at the right time—so as to be able to harvest such an amazing animal with my bow. If I allow myself any sense of pride, it derives only from the fact that I never gave up in my battle against Murphy. On May 18, 2004, the assassination of his ghost was quick and clean, all right, but the question in my mind was: would it remain permanent? Somehow, I doubted it. After all, ghosts do have away of surviving death, don’t they?

Would my World’s Record remain permanent? Hardly! I expected that within a few years it would be eclipsed, and probably by a spring bear taken along that same section of Northwestern Alaska coastline. I have no doubt the monster griz that just about blew over the top of me there in May 2003 was, himself, significantly larger than my World’s Record taken a year later. As the cliche goes, “Records are made to be broken,” and sure enough, in April 2015, a Pennsylvanian named Rod Debias saw his beast of an old boar dethrone mine at the biennial Pope and Young Convention in Phoenix, Arizona. He had, indeed, arrowed his monster with the same outfitter I had used, and on the same stretch of Alaska coastline. At least I retain the satisfaction of knowing that my bear was dethroned by a truly worthy challenger. It just so happens—believe it or not—that the Debias bear, the new Pope and Young World’s Record Grizzly, scores higher than any grizzly ever taken by a rifle hunter! It sits atop all firearm-killed grizzlies ever entered into the All-Time Boone and Crockett Records. Dr. Saxton Pope and Art Young must feel so proud!

Editor’s note: This article is the sixtieth of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work, and the various editions of BAREBOW! available, by clicking here:http://www.barebows.com/. You can also follow BAREBOW! on Facebook here.

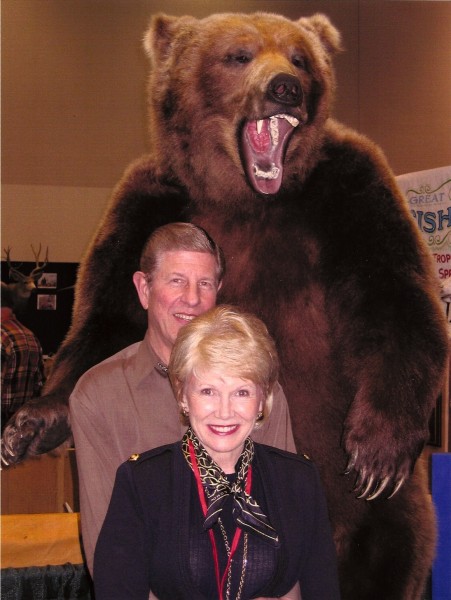

Top and featured image courtesy of Dennis Dunn