A Different Way To Build Your Off-Grid Log Cabin

Jordan J. 10.25.23

Like many of you, I have dreamed of building a log cabin in a remote location, using timber from the land, and establishing a place of peace, tranquility, and outdoor recreation.

About two years ago, I committed to this dream. Along the way, I discovered a different style of building log cabins that worked well for me. While it’s a departure from the traditional, “Lincoln log” or “little house on the prairie” building method and probably won’t be endorsed by the Timber Framer’s Guild of America, the results are functional, solid, and aesthetically pleasing.

Background: Impossible Expectations

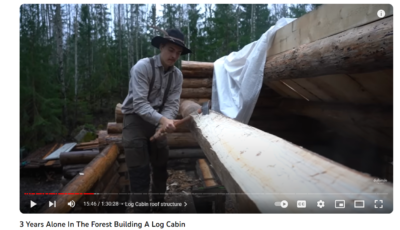

If you’ve researched building a log cabin, you’ve probably come across this video:

“3 Years Alone In The Forest Building A Log Cabin” tells the montaged story of Erik Grankvist, an extremely dedicated and talented outdoorsman who went out to “build my own traditional off grid log cabin by hand from the materials of the Swedish wilderness. Just like our ancestors.”

The results are breathtaking.

And intimidating.

If you’re like me and don’t know if a Gransfors Bruk is an Ikea end table, the amount of talent and hard work exemplified in this video can feel like an insurmountable challenge.

Initially, I attempted to build a log cabin like Erik, but I ran into several problems that sent me looking for an alternate method.

During my initial attempt to build a log cabin the traditional way, I discovered two challenges that made me seriously question if I had what it took to build a log cabin.

Challenge #1: Peeling logs is one of the hardest chores you’ll ever do.

You can’t leave the bark on a log if you want your cabin to be insect proof and last more than a few years. This is especially true if you’re using pine, which invites all manner of beetles and borers under its skin as soon as it’s felled. However, I quickly discovered that peeling logs is brutal work, and huge respect to Erik and anyone else who’s peeled enough logs for an entire cabin.

I tried various methods for peeling logs. If you decide to go this route, the best methods I discovered were using the Bully Floor Scraper tool and the chainsaw Log Wizard attachment, which a relative was kind enough to get me for Christmas. I can tell you that both of these methods were much more effective than using a potato peeler.

I did not purchase the $305 Gransfors Bruk draw knife used by Erik Grankvist to peel his logs, and this was probably a mistake. It looks like an amazing, quality tool.

I started peeling logs in September of 2021, and peeled logs all the way through December:

By the end of the year, I had about 30 peeled logs — only about a third of what I’d need, according to my rough estimate.

However, when it was time to start stacking lincoln logs, I quickly discovered that:

Challenge #2: The straightest logs I could find weren’t straight at all.

I certainly selected the white pines that looked the straightest. When I was peeling them, they seemed pretty straight.

However, when I started laying them together, I quickly discovered how curved many of them were:

The log lying on top may not look too bowed, but when these kinds of logs are laid on top of eachother, the curves create all kinds of irregular gaps, like the 4-6 inch gap below:

A 4-6 inch gap isn’t trivial, and it causes problems for the next log, and the next — eventually compounding if they are not dealt with at each layer.

There are two ways to deal with these large gaps. First, you could apply large amounts of mortar, mud daub, or chinking compound between the logs to fill in the gaps, as is often seen in historic log cabins:

I knew I’d need to do some gap-filling, but 4-6 inch gaps were just more than I wanted to tackle, for both logistical and aesthetic reasons.

A second option is to do what Erik Grankvist did and meticulously hand carve/shape each log to fit together perfectly:

‘

‘

Regrettably, I do not have the kind of woodworking skill Erik has to pull that off. I consoled myself with a the belief that Erik’s trees were straighter than mine (Swedish lodge pines?).

My Solution/Hybrid Technique

After realizing that I was either going to need to cart in mortar/chinking compound by the 55 gallon drum or become a master timber crafter, I decided to give up and take the easy way out.

This “easy way” consisted of buying an Alaskan Chainsaw Mill and milling one hundred and forty four 2X4’s and 60 other odd planks between January and May of the next year:

I said to myself: “If I’m going to have to mill each log to fit nicely together, why not just mill lumber?”

Instead of building a “log cabin,” I retreated to the less noble goal of building a “cabin made with logs,” stick-built out of milled lumber. It’s kind of like when the label on your “natural” food product says it’s made WITH “natural flavors.”

However, a by-product of lumber milling is that for each log milled, you end up with four live edge semi-round slabs. Once I framed the cabin from home-made 2X4’s, my plan was to use these slabs as siding on the framed structure, completing the faux log-cabin look.

How it Went

The plan went well:

I used Perma-Chink log cabin chinking compound to seal the seems between log siding slabs. It didn’t look too bad:

I paneled the interior wall cavities to give the chinking compound a backer, and also for aesthetics. I may insulate the stud cavities later, depending on how well the space can be heated with the Dwarf 4K wood stove I installed:

Concluding Thoughts

After I finished the milling and prep-work stage, I began actual construction in September of 2022, and am now in the final stages of adding solar power, rainwater collection, an outhouse, and other off-grid amenities — a little over a year of total build time. And in that year, I was only able to work on it one day a week for most weeks, for an approximate construction time of less than 52 working days. Additionally, I had no on-site power, so except for the chainsaw and a battery operated drill, all nails had to be hammered by hand and all boards cut with a handsaw.

Given these constraints, I feel that my hybrid technique enabled me to create the log cabin much faster than if I’d adhered to traditional building methods. It’s a trade off for sure, one that will bring inevitable disappointment from log cabin purists.

But at least now I have somewhere to sit peacefully and read Walden Pond: