Despite Their Thick Skins, Alligators and Crocodiles Are Surprisingly Touchy

OutdoorHub Contributors 11.14.12

httpv://youtu.be/3A5yApwIUos

Crocodiles and alligators are notorious for their thick skin and well-armored bodies. So it comes as something of a surprise to learn that their sense of touch is one of the most acute in the animal kingdom.

The crocodilian sense of touch is concentrated in a series of small, pigmented domes that dot their skin all over their body. In alligators, the spots are concentrated around their face and jaws.

A new study, published in the Nov. 8 issue of the Journal of Experimental Biology, has discovered that these spots contain a concentrated collection of touch sensors that make them even more sensitive to pressure and vibration than human fingertips.

“We didn’t expect these spots to be so sensitive because the animals are so heavily armored,” said Duncan Leitch, the graduate student who performed the studies under the supervision of Ken Catania, Stevenson Professor of Biological Sciences at Vanderbilt.

Scientists who have studied crocodiles and alligators have taken note of these spots,which they have labeled “integumentary sensor organs” or ISOs. Over the years they have advanced a variety of different hypotheses about their possible function. These include: source of oily secretions that keep the animals clean; detection of electric fields; detection of magnetic fields; detection of water salinity; and, detection of pressure and vibrations.

In 2002, a biologist at the University of Maryland reported that alligators in a darkened aquarium turned to face the location of single droplets of water even when their hearing was disrupted by white noise. She concluded that the sensor spots on their faces allowed them to detect the tiny ripples that the droplets produced.

“This intriguing finding inspired us to look further,” Catania said. “For a variety of reasons, including the way that the spots are distributed around their body, we thought that the ISOs might be more than water ripple sensors.”

As a result, Leitch began a detailed investigation of the ISOs and their neural connections in both American alligators and Nile crocodiles.

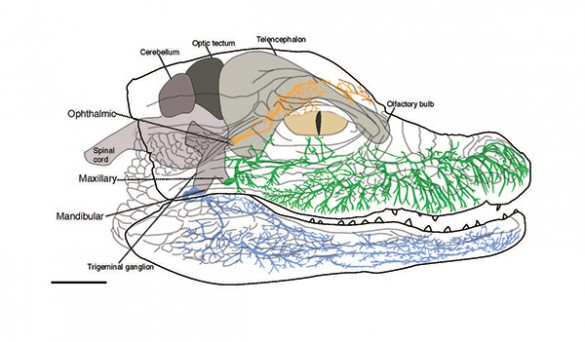

Leitch found that these sensory spots are connected to the brain through the trigeminal ganglia, the nerve bundle that provides sensation to the face and jaw in humans.

In addition, his studies ruled out most of the alternative hypothesis for the ISOs function. For example, his anatomical studies didn’t find pores that could release cleansing oil. Similarly, he found that the nerves in the ISOs didn’t react to electric fields or, when submerged in water, to changes in salinity.

“I didn’t test for sensitivity to magnetic fields, but we don’t think this is likely either,” said Leitch. In animals that can detect magnetic fields, he explained, the sensors are located inside the body, not on the surface.

What he did find is a diverse collection of “mechanoreceptors:” nerves that respond to pressure and vibration. Some are specially tuned to vibrations in the 20-35 Hertz range, just right for detecting tiny water ripples. Others respond to levels of pressure that are too faint for the human fingertip to detect.

Their analysis led the scientists to conclude that the crocodilian’s touch system is exceptional, allowing them to not only detect water movements created by swimming prey, but also to determine the location of prey through direct contact for a rapid and direct strike and to discriminate and manipulate objects in their jaws.

Their finding that the most heavily wired ISOs are located in the mouth near the teeth suggests that the touch sensors help the animals identify the objects that they catch in their jaws. The sensors also appear to provide the sensitivity that female alligators and crocodiles need to delicately break open their eggs when they are ready to hatch and to protect their hatchlings by carrying them in their jaws, the same jaws that can clamp down on prey with a force of more than 2,000 psi.

httpv://youtu.be/rMCYzwdE39M

This research was supported by National Science Foundation grant #0844743 and by a Vanderbilt University Discover Grant.