The Toxic Chemical Blues

James Swan 07.29.13

I woke up this morning, to my clock radio. The announcer man was telling a tale of great woe.

There’s poisons all around us, he did declare. They’re in the soil, the water and the air. Acid in the raindrops when they fall, and carcinogenic chemicals in my kids’ schoolroom walls.

DDT, PCB, EDB, and mercury, they’re after me. Where can I go, and what can I do? Seems like you just can’t get away from the toxic chemical blues.Lyrics to “Toxic Chemical Blues” by James Swan, c&p, ASCAP.

Sound like you? Seems like every day there is a warning about something new.

If you’re planning a fishing trip, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), nearly half of U.S. lakes and reservoirs contain fish with potentially harmful levels of the toxic metal mercury. When it’s present in sufficient quantities, mercury can damage kidneys and the nervous system, and interfere with the development of the brain in unborn children and very young children.

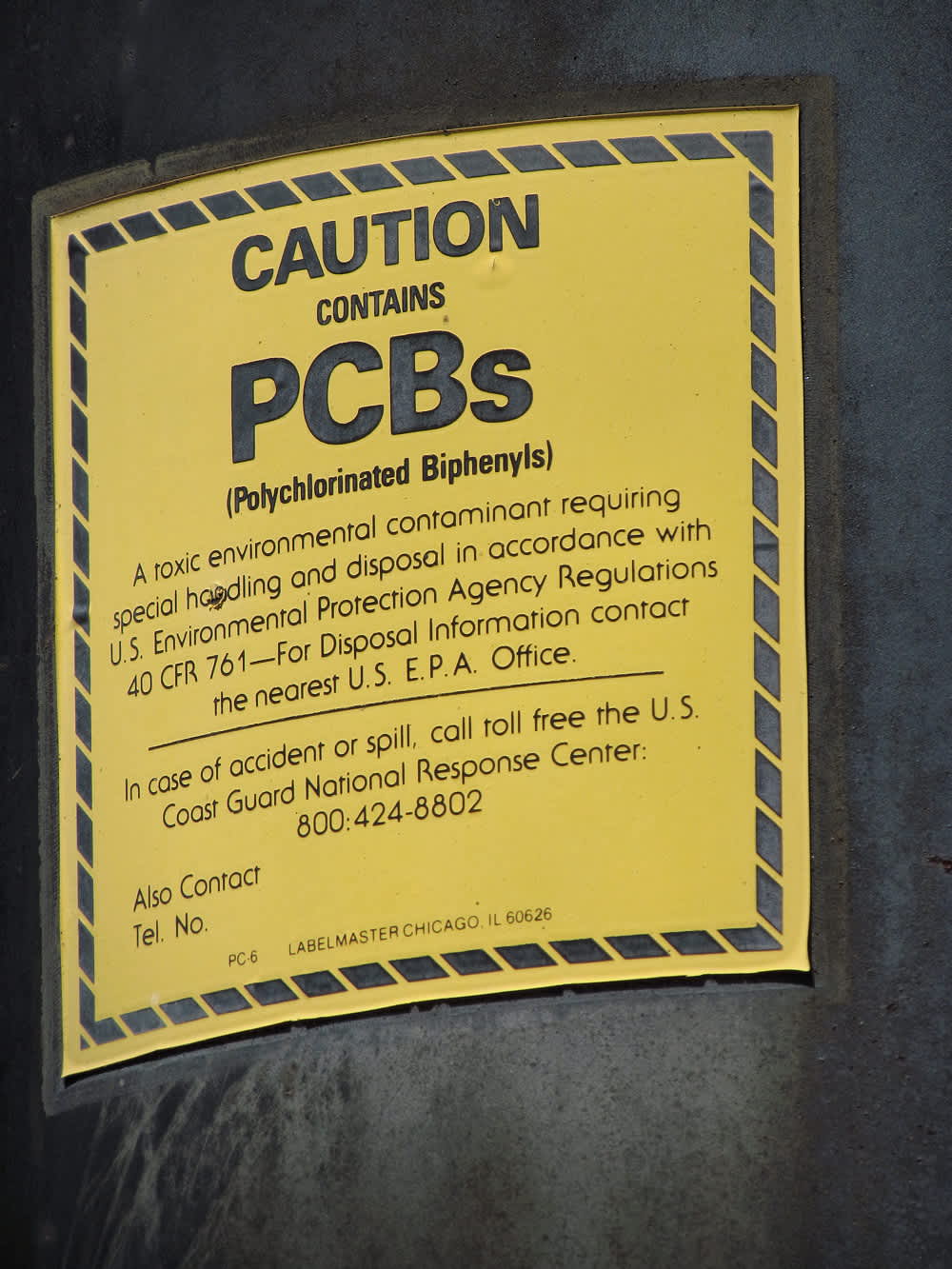

About 17 percent of the lakes EPA tested had fish contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) in excess of accepted levels. PCB is a persistent organic pollutant that was used in electronics and coolants. It was banned in manufacturing in the U.S. in 1979 as it was found to be carcinogenic–cancer-causing–but residuals still can be found today.

The EPA stats sound grim, especially when in 2004 the EPA said that one of every three lakes in the United States, and nearly one-quarter of the nation’s rivers contain enough pollution that people should limit or avoid eating fish caught there. Are we losing the battle?

Suffering from the toxic chemical blues, I sought wise counsel with Dr. Richard Wade, a friend for many years who has served as the head of public health agencies for the states of Minnesota and California, once was in charge of environmental health for the Princess Cruise Lines, was the director of Emergency Response and Risk Management Services for International Technology Corporation, and today is an occupational and environmental health consultant with Exponent as well as a Clinical Professor at UC Irvine

Two of Richard’s “trophies” are leading the charge on getting ethylene dibromide (EDB) banned in California, and directing the environmental health operations for the cleanup of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound.

When Dick was the Director of Environmental Health for Minnesota, he issued a warning about eating perch and pike based on elevated levels of mercury in samples of fish his department found. All hell broke loose. Minnesota is fisherman’s paradise. To make the point that “Poison is function of dose,” Wade held a press conference in the dead of winter at a resort that’s only accessible by snowmobiles, where everyone present, including Wade, consumed a meal of walleyes.

Wade explained that while mercury can arise from industrial sources, it’s a naturally occurring substance usually present in very small amounts. When ingested in very small amounts, our body can rid itself of mercury (pdf).

What seems to have happened in pristine northern Minnesota was that acid rain changed the pH of the water, thus reducing the natural processes for breaking down metallic mercury in rocks and soil. Small aquatic organisms fed on the mercury-enriched sediments, transforming metallic mercury into methylmercury. When the big fish ate the little guys, they accumulated most of their mercury in their flesh.

People were on the receiving end of all the mercury that everything else had eaten. It was not an enormous amount, but it did exceed public health standards for young kids, born or not, who are more susceptible to damage from toxic exposures.

Toxic poisoning can be both acute and dramatic or slow, gradual, and accumulative. Acute poisonings are relatively easy to spot. Wade said that mercury probably has always been present in large oceanic predator fish. Many of the warnings these days come about because, “In the last twenty years we have made quantum jumps in detection,” both in the environment, and in humans, sometimes revealing previously unidentified potential chronic toxic poisoning potentials.

I understand that one. Growing up on Lake Erie, I ate a lot of perch and walleyes. Later we learned the fish were laced with mercury. Baldness is a symptom of chronic mercury poisoning, and I have scant few hairs on my head. Is my being follicularly challenged hereditary, a sign of virility, or due to eating too many Lake Erie fish?

Most of us try to forget about dilemmas like this, if we can. Some people become obsessed with the fear of poisons, succumbing to a modern psychological malady–toxiphobia–which is an obsessive-compulsive disorder, which includes the constant need to wash hands and fear of germs.

Wade advises that each person develop their own filtering system to think critically about toxics. Some of the basics of evaluating toxic warnings:

- Each person’s tolerance for toxics is different. Some people are more susceptible than others, especially young children and pregnant mothers.

- “Poison is a function of dose.” Acute poisonings are rarer these days, but with more sophisticated monitoring, we are more aware of chronic poisoning situations. Some things we eat in small amounts are good for us, like iodine. Swallow a bottle and you are poisoned.

- Always question the source of the warnings. A number of environmental groups are dependent on crises for funding. If there isn’t a real one, they may make it up to keep themselves in the spotlight and their funding coming in.

- Minute quantities of some substances–parts per million or even parts per billion–can cause delayed toxic reactions, especially if they do not rapidly biodegrade. Remember how DDT did not kill predator birds like Bald Eagles or Peregrine Falcons, but caused thinning of their eggshells, which meant that incubating birds crushed the shells of their young. What does low-term chronic DDT accumulation do to people? No one is quite sure. The question is do you want to wait to see if it just affects birds, or do you see the birds as a warning sign of what is possible for people?

I asked Dick Wade if he ate fish. “Not large pelagic ones like shark or swordfish. Small ones, like cod and salmon, sure,” he added, noting that he loves to fish.

Let’s not forget some good news. Mercury in the sediment cores from inland lakes within the Great Lakes region have decreased by about 20 percent since the mid-1980s. And, mercury concentrations in walleye, largemouth bass, lake trout, and herring gull eggs in the Great Lakes region are also declining (pdf).

Sportsmen should be more aware of toxic chemicals than most. Every state has issued fish consumption advisories covering at least some of their lakes or rivers, and those advisories are printed in the fish and game regulations. They generally will tell you how many “meals” (eight ounces) of that species in a certain body of water they feel is safe to eat per month. In general, the most nasty stuff accumulates in the biggest fish, and those that are bottom feeders, like carp and suckers.

If you really want to find out what’s going on with the safety of eating fish in waters you frequent, check with your state fishing regulations. EPA also has a national list of fish advisories on its website.

In addition, the FDA recommends that “women of childbearing age and young children avoid those species of fish and seafood known to contain high concentrations of mercury. For women and young children, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) currently recommend against eating any shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and tilefish, and also limiting consumption of albacore tuna to one meal per week.”

You can reduce the amount of most all persistent pesticides when cleaning your fish. Remove skin, fat and internal organs and DDT, PCB, and so on will largely be gone. Mercury accumulates in the muscle tissue, which is what you eat.

Regardless of all these warnings, you still can fish and catch and release. And, the EPA and the USDA have reported that fish in Alaska have mercury levels far below other places in the U.S. so maybe the warnings will inspire you to plan your next trip to the Pacific Northwest and Alaska to stock up the freezer on salmon, halibut, mackerel, and cod. It always helps to have a good dream or two.

Another way to cope with the toxic chemical blues

In an effort to clean up toxic wastes, many cities and some environmental groups have created special places where you can drop off old toxic chemicals. Some of these places aren’t properly run or protected. Earlier in our careers, both Dick Wade and I consulted with federal agencies on environmental health and possible terrorism. In conversations with Dick aided by a toxic chemical called “beer,” we fantasized about what could happen if a group of terrorists got hold of some of the common toxic pesticides that end up sitting in storage in some of these clean-up centers.

Combining that scenario with my interest in game wardens, I’ve written a techno-thriller novel, LD-50, about a federal game warden that uses modern science and ancient wisdom to catch a terrorist who is using old pesticides as toxic weapons. Wade checked out the science in the novel and says that it’s valid, so this is grounded fiction that some other reviewers have enjoyed.

To my loyal readers at OutdoorHub, I’d like to make you a special offer. You can download the book as an eBook from Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, etc. for $4.95. BUT, if you go to Smashwords, you can get the book half-price, $2.48, by using this Coupon Code: LY39Q. The offer expires August 16, 2013. See reviews and a book trailer here.