The BAREBOW! Chronicles: On the Edge of Space

Dennis Dunn 10.16.13

I had heard it said that to hunt Rocky Mountain goats with a bow was to take your life in your hands. At least in the Cascades of Washington State, where the mountains tend to be more vertical than diagonal, I could understand the basis for such probable hyperbole. I guess I never really believed that, or took the warning seriously, however, until the events of Saturday, November 1, 1973.

It was the final weekend of the archery goat season in the Goat-Davis Mountain Area, and the entire region had been blanketed Friday night with about 14 inches of dry powder snow. All day Friday it had rained steadily. Following the onset of evening, the temperature had dropped precipitously under the spur of a northern cold front, so the fresh snow which greeted me Saturday morning concealed a thoroughly treacherous and nearly uniform layer of water-ice underneath it all. So intimidating were the conditions, in fact, that—if it had not been for my hard-to-draw goat tag being about to expire—I would have simply turned around and driven back home.

Earlier in the season, Indian summer conditions had prevailed, and I had already spent a glorious nine days hunting in the area. The mountain goat population in Area 27 was one of the highest in the state, and I had seen and photographed numerous goats up in the higher parts of the unit during the month of September. The right circumstances, however, had never quite come together to allow the taking of my trophy goat with a bow. Several shots that didn’t quite hit their mark had also contributed to my tag remaining unfilled. I had hoped to make it back up into the area for a weekend or two in October, but it was the political silly season, and my full-time job as the elected Chair of the King County Republican Party prevented me from returning to “God’s country” until the first weekend of November.

Given the heavy, fresh snowfall on the season’s final Saturday, I knew I had to find a goat relatively low down, and that my best chance would be to drive the Fish Lake Road and scout the steep northern flanks of Goat Mountain. The morning dawned clear and very cold. Around 8 a.m., I spotted a pair of goats (looking very yellowish against the total whiteness of the new snow) feeding approximately 1,000 feet above me on a small ledge suspended directly over some nearly-vertical cliffs. Hunting alone, and knowing the terrain I was facing was likely to be far more dangerous and difficult than it would have been the day before, I filled my backpack with more clothing and survival gear than usual.

Fortunately, before leaving home, I had thought to throw a 200-foot length of mountain-climbing rope in my car, but as I waded the small river and started to gain elevation, I realized I was cussing myself for having forgotten to bring my crampons, as well. As it turned out that day, it was a very lucky thing I had made mountaineering my principal recreational activity during my four years of college. Otherwise, I would likely not have survived the events that were about to unfold.

The pack on my back and the bow in my hand made it hard to cope with the nearly knee-deep snow and the icy rocks hidden below. A couple hundred yards to the left of the goats was a break in the cliffs that looked as if it might afford access to my quarry. Yet the going was painfully slow—nearly every step of upward gain was matched by an intervening one where the boot would not hold its grip on the slippery surface that was so well concealed underneath the innocent-looking white blanket. Every bit of vegetation was welcomed as a gift from heaven, but there were long stretches of unbroken whiteness.

After more than four hours of probably the most treacherous climbing I had ever done in my life, I finally reached the base of a narrow chute which led upwards through the same set of cliffs I had glassed from the road below. On three separate occasions during the ascent, I had nearly peeled off the side of the mountain, and as I worked my way up the last 50 yards of the chute, the thought of suddenly becoming a human bobsled or toboggan was something I fought desperately to force from my mind. At long last, around 1 p.m., I discovered the two goats once again—about 100 yards away, feeding in almost the identical location where I had first spotted them five hours earlier.

Once at the top of the chute, the going became much easier, and after dropping my pack and drinking at least a quart of water, I quickly worked my way laterally to a point of concealment some 30 yards above the unsuspecting goats. The smaller one was not visible from where I knelt in the deep snow, but I could just see the long back of the larger one as it pawed for food in the bottom of the tiny basin directly below me. While moving into position, I had lost track of the smaller goat, and, as I silently “kneed” my way down the slope through the dry powder toward the rim of the little cup containing my prize, I had an uneasy feeling that something I wasn’t quite ready for was about to happen. In anticipation of imminent action, I had removed my outer glove from my shooting fingers and placed an arrow on the string of my old Bear Archery recurve.

All of a sudden, the missing critter sat up abruptly on its haunches not more than five yards in front of me and gazed out over the valley! He had been bedded just below the lip of the hollow. As I arrested my motion and “froze” in my knee-prints, the animal turned its head and looked at me as if in utter disbelief. What followed was a staring-down contest that lasted a good 10 minutes and caused me to choke on my heart more than once. I knew if I spooked this goat, my chances of taking the bigger one would be slim.

The contest was both frightening and comical at the same time. When I had dropped my pack earlier, I had tied a camo bandana around my face, and now I was suddenly trying to win this “stare-athon” by closing one eye, and by squinting at my adversary with the other eye half-shut (two open eyes will give you away every time). My worthy opponent tried many tricks himself to try to get me to give myself away—including going through the motions of feeding and then jerking his head up quickly in an effort to nail me doing something I shouldn’t be doing. Like breathing! Or blinking!

I guess in the end that goat must have concluded I was simply some strange kind of bush that had sprouted overnight. After what seemed like an eternity, he slowly shuffled down out-of-sight to join his companion. The bitter cold had turned my fingers completely numb during the showdown, and, as I quickly slid forward on my knees toward what I knew would be the moment of truth, I wondered if they still had enough strength left to draw my bow and make a decent release. One slow look over the edge told me I was about to find out.

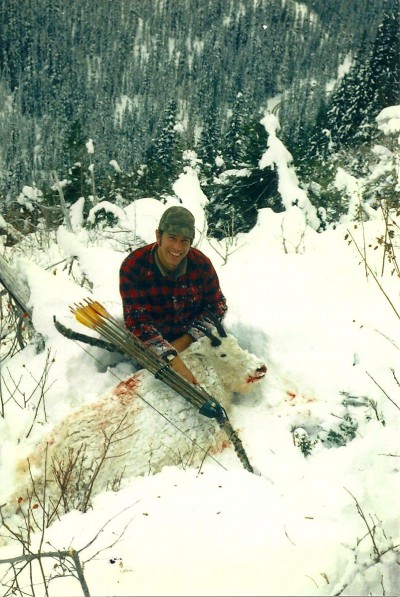

Both goats were 20 feet below me, walking slowly up a steep trail and obviously intending to exit the basin around 10 yards to my left. I had precious little time in which to act. The goat I wanted was in the lead, and as it neared the top of the rise, going directly away from me, I quickly rose, drew, and released one of the most perfect arrows I have ever shot during my hunting lifetime. The arrow entered right behind the front shoulder, right next to the spine, and passed through and out the center of the chest. The animal increased its gait only slightly, and, after five seconds had passed (I was counting), it suddenly died on its feet and tumbled off a ledge into a narrow snow bank just below it.

I was extremely lucky he stopped where he did, because—had he slid even five feet further—he would have disappeared over the edge of the drop-off and only come to rest some 800 vertical feet below. Had that actually happened, my fingers might have sustained some real frostbite, but the field dressing of the animal right there on the spot allowed me to warm my hands up inside the goat’s body, and I have never been more grateful for small or large favors than I was on that frosty afternoon for the precious gift my Rocky Mountain goat made me of his very life’s blood.

Once the field dressing was finished, I began to contemplate seriously the real dangers that still lay ahead before nightfall. Any alpinist will tell you that descending a steep mountain is virtually always more difficult and dangerous than climbing up the same mountain. Unless, of course, you have a rope you can use for rappelling! Given the nature of the “under-carpet” beneath the snow blanket that was covering my particular peak, I knew trying to descend the way I had come up would be tantamount to suicide. Thank God I had brought the rope up with me!

The real challenge, needless to say, was how to get myself and the goat down the one and only rope I had to work with. Carcasses have exceedingly limited rappelling ability, and the nearly vertical cliff directly below us was going to have to be negotiated in segments of no more than 70 to 90 feet at a time. The 200-foot rope couldn’t simply be tied off on a tree trunk at one end; it had to be doubled so it could be retrieved at the bottom of each section of the descent.

The technique I developed out of harsh necessity actually worked pretty well, after a bit of trial and error. At least there were no fatal errors! I would tie the goat securely to one end of the rope, and then—taking three wraps around the base of a stout, upthrust shrub or alpine fir—I would lower the animal to near the midpoint in the length of rope. Or at least until the “payload” reached a little ledge, or some other little tree or bush in that vicinity down below. Next, throwing my half of the rope toward the valley floor, I would shinny down it while my trophy served as the counterweight. Once I caught up with the goat again, then I’d pull the entire rope down from above and start the whole process all over. I don’t recall any longer just how many segments it took, but—if anything—the total descent proved even more difficult than the climb up. Somehow, by the Grace of God, my prize and I both reached the river in one piece just before dusk.

Fording the stream with a whole goat on my shoulders was the last obstacle left between me and the security of car and home. Adrenaline is a wonderful thing! As I labored the last few yards up the bank to the edge of the road, my sense of exhilaration was more than a match for my physical exhaustion. I knew that my safe return from the edge of space was an even more precious victory than the Pope & Young head that would soon adorn my living room wall.

Editor’s note: This article is the ninth of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks–join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the eighth Chronicle here.