The BAREBOW! Chronicles: A Montana Chipmunk

Dennis Dunn 04.30.14

It was more than eight years after the harvest of my first cougar before I again found myself under a tree with a lion in it. The planning for the hunt began in Traverse City, Michigan at the April 1995 Pope & Young Convention. Montana outfitter Mike Parsons (Crow Creek Outfitters) had most generously donated a cougar hunt to the Club’s biennial fundraising Conservation Auction. For reasons I no longer recall, I found it necessary to reschedule the hunt for one year later, but sometime around December 10, 1996, I arrived one evening at Mike’s ranch, not far south of Helena, with high hopes of our being able to find and tree a trophy-class tom. I had already learned many times—the hard way—that it would not be easy, and that we would need some luck, as well.

The next morning, we loaded the hounds and the Ski-Doos onto Mike’s truck and trailer and set out for an area east of there near White Sulphur Springs. Mike had a little cabin in the hills nearby from which he liked to hunt the big cats. There were about six inches of fresh powder snow on the ground, so conditions seemed ideal for scouting up some fresh lion tracks. Unfortunately, though there were a few tracks around, they all seemed to belong to young males, females, and kittens. Mike knew I was looking for a big tom and didn’t want to settle for anything less. We put in many hours and miles every day for a week, scouring the country on our snowmobiles, but we never did run across a track worthy of pursuit with the hounds. By the end of seven days, the fresh snow we’d had to work with at the start was disappearing, and what remained was covered with such a hodgepodge of old animal tracks and snow “kerplops” that it was often hard to tell what we were looking at. Mike suggested I head home for the Christmas holidays, and that I return a week or so after New Year’s—providing there were fresh snow to work with at that time.

So, as soon as the last of the New Year’s Day college football games had been decided, I gave Mike a call to find out what the conditions might be like for my return visit. He told me they hadn’t had a lot of snow since I’d left in mid-December, but the good news was that a storm was expected to blow in toward the end of the week, so I could start driving his direction anytime I wanted after January 6. That worked well for me, and I seem to recall that our second hunt got underway around January 9.

Mike Parsons is one of the nicest guys and hardest-working outfitters you could ever hope to meet. He is also an avid archer, a longtime Pope & Young Club Member, a dedicated fair-chase sportsman who has harvested many outstanding trophies of his own with a bow, and he is a houndsman extraordinaire. One of the great joys in his life is training dogs for lion hunting, and working with them on a regular basis in pursuit of the big cats. Hound music, to his ears, is more beautiful than any symphony or opera ever thought of being!

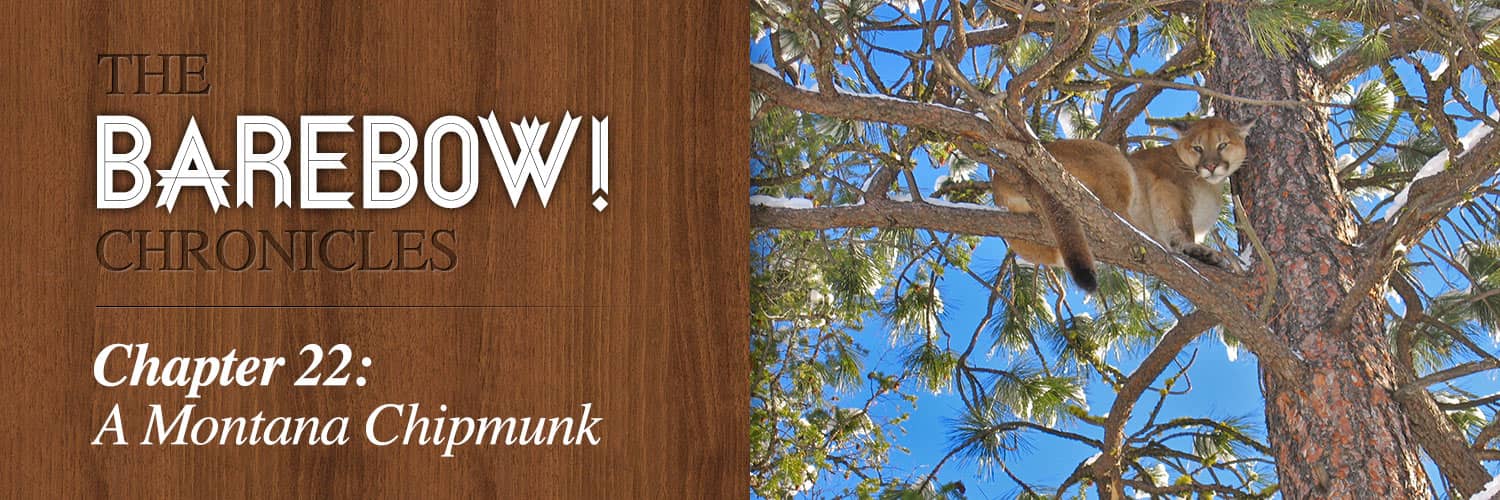

On my return hunt with Mike, I believe it only took three days before he found a track he felt was worth putting the hounds on. Soon the chase was underway, and the dogs were barking “treed” within five minutes after leaving their box on the snowmobile trail. As I recollect, we had to work our way up a steep, timbered slope about 400 yards to the big spruce tree which held the cougar. He was comfortably ensconced on some limbs about 30 feet off the ground, staring down at us and the yelping dogs with a look of calm disdain. A quick glance at the lion’s posterior from below confirmed that he was, indeed, a male. After snapping a few pictures with my still camera, and tying down the hounds on the uphill side of the tree, Mike and I got serious about trying to decide if this was a tom that would score the requisite 13 and 8/16 inches for entry in the Pope & Young Records Book.

I had told Mike, when I bid on the hunt at the Club’s 1995 Biennial Convention, that I didn’t want him to let me shoot any lion that he didn’t think would score a minimum of 14. That was to be the benchmark, and it gave us a fair amount of room for error. My guide walked around the tree several times, attempting to view the cat’s head and body from every angle. To me, the body seemed quite stocky, and the pumpkin-shaped head appeared a bit like that of a giant chipmunk whose cheeks were crammed full of nuts. Ultimately, I knew I had to leave the decision to Mike. He had seen many times more lions up close than had I.

Finally, I couldn’t stand it any longer and blurted out the question: “Well, do you think he’ll go 14?” I asked with bated breath.

“Yeah, I don’t think there’ll be any problem,” came back the reply. “He should score at least 14, anyway,” were Mike’s last words on the subject.

“Great!” I said. “Then it’s time for me to see if I can’t thread the needle up there and put an arrow right through his vitals.” The big tom had moved around to the other side of the trunk, and it took a little maneuvering on my part to get myself into just the perfect position so that I could have a clear path to the underside of his rib cage. A triangular opening about eight inches on a side (formed by limbs lower down) seemed to be my best bet, so I drew back, took careful aim, and let fly. The instant pass-through proved an ideal hit, and in less than 10 seconds the heavy cougar came crashing down through the branches to the ground. After the impact, nothing. His tawny form was lifeless, and it was time for a quiet handshake and a silent prayer of thanksgiving.

A few hours later, after getting our trophy lion back to the Ski-Doo, then to the truck, and finally back to Mike’s ranch, we put him on a scale in the garage. With a totally empty stomach, he weighed in at 136 pounds. The next task, after butchering him up for the meat, was to skin out the head, so that the skull could be measured “green,” as we say. When we at last got everything down to the bare bones, the tape measure came out, and the length and width were added together for the composite score. Mike and I suddenly stared at each other in disbelief! Twelve and 15/16?! Neither of us could believe it, so we measured the skull all over again—with the same exasperating result. “Well, I’ll go to hell!” Mike exclaimed.

“No, I wouldn’t wish that on ya,” I returned. “But how in thunderation could we have so badly misjudged him? That’s what I don’t understand! What a big body for such a small head! He must still be a pretty young cougar—probably no more than a teenager,” I concluded, unable to mask the deep disappointment in my voice.

“You may be right, Dennis,” was Mike’s response. “I’ve never been this badly fooled by any lion in my life. I felt sure he’d go 14!”

We both fell silent for a bit, and then Mike added an interesting thought. “If this cat weighs 136 pounds, with no venison in his tummy, as a teenager [two or three years old], just imagine what he might have weighed if he’d lived to be seven or eight!” I nodded my head in agreement. Mike was clearly embarrassed, and I felt badly for him—more for him than for myself. To this day, we still laugh together about how badly fooled we both were by that gargantuan, super-healthy, Montana chipmunk. Nearly one year after the hunt ended, I received the mandatory tooth-study report from Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. The teenage tom had been aged at two.

Editor’s note: This article is the twenty-second of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the twenty-first Chronicle here.

Top image by Dennis Dunn