The BAREBOW! Chronicles: Todagin Mountain, 1991

Dennis Dunn 06.30.14

Some readers who are avid hunters may wax skeptical about my reasons for moving to British Columbia in the fall of 1988, but I want to assure them it was not so I could hunt Stone sheep for the price of a resident’s $50 tag. Not that that’s a bad reason for moving there, mind you, but it wasn’t my reason at the time. I had bigger fish to fry. Actually, I guess the better metaphor would be that I had bigger game to pursue—under the rules of Fair Chase. I was in between marriages, and I was hunting all right, but I was hunting for the right lady with whom to spend the rest of my earthly life.

On day number six, following my arrival in BC, I found her in the city of Vancouver. It is a great city for hunting, if you know what you’re hunting for, and I certainly did—or at least I did as soon as I set eyes on her. Call it serendipity; call it God’s Grace or His Grand Design. Yet whatever you choose to call it, I call myself the luckiest man I’ve ever met. I had just taken a three-month consulting job with a junior gold-mining exploration company in Vancouver, but—thanks to Karen—I ended up spending eleven years living in that beautiful city as a Landed Immigrant of Canada. Being able to hunt and fish BC as a resident was a terrific bonus, but it was strictly secondary to my intention of helping Cupid become a better archer.

I admit to being pretty dense on occasion, and I have to say that it took nearly two years of living in Vancouver before the light bulb finally exploded in my brain: I could actually bowhunt Todagin Mountain on my own! I’d been shooting my bow for some time at the indoor lanes of Boorman Archery in nearby New Westminster, and during the winter of 1990-1991 I chanced to meet there a recent German immigrant named Martin Kobler.

The two of us began to talk bowhunting whenever we’d meet at the lanes, or at weekend 3D shoots, and it wasn’t long before I asked Martin if he’d like to join me on a bowhunt for Stone sheep the first 10 days of August. I told him of my experience on Todagin in 1986, and soon we were busy planning our menus for the trip and reorganizing all our backpacking and camping gear. I ordered a two-week supply of freeze-dried food from the States—more than I figured we’d need. All spring, and into late July, we practiced shooting arrows every couple of days, and by the last week of July, we were pretty psyched up for sheep hunting, to say the least.

The long, two-day drive up to Kiniskan Lake in my Subaru wagon brought us to the boundary of the hunting unit three days before the season-opening of August 1. We wanted to have at least a couple of days for scouting up in the high country before the season actually started. During my hunt with Bruce Creyke in 1986, I had noticed that there was a large ranch situated right at the foot of the long, main, southwest buttress-ridge of the mountain. It had struck me then as an outstanding way to gain access to the high plateau of the peak, which seemed otherwise girdled by very steep slopes all around. I had learned from the folks at the Tatogga Lake Resort a few miles further up the road that the ranch was owned by an old fellow named Adams, who had homesteaded the place nearly 50 years earlier.

When Martin and I found the dirt road turning off the highway and leading to the ranch house, we had high hopes of persuading Mr. Adams to let us park our rig at the far end of his ranch, right underneath the mountain. The old fellow, who I figured had to be in his mid-seventies, was very friendly and invited us to come into his living room and sit down for a talk. As sparsely populated as his part of the world is, I had the feeling he was just glad to have a little social contact with other members of the human species. After sizing us up for a while, he granted the permission we were seeking, so (along with a big thank-you) I gave him a $50 bill, just to seal the deal.

We slept on the ground next to our wagon that night, and a million stars stared down on us with such intensity I found it very hard to get to sleep. Of course, the anticipation of the adventure about to unfold had something to do with that, no doubt, and all the moving satellites and shooting stars contributed, as well.

Perfect weather was the order of the next day, and we wanted to get as early a start as possible to avoid the heat. Loaded with bows, arrows, cameras, optics, extra clothing, personal effects, a good tent, cookware, and other community gear (plus our 10-day supply of food) we estimated our backpacks each weighed around 65 to 70 pounds. The climb up to the rocky fortress (known as “the Citadel”) that crowned the top of the southwest buttress-ridge took us over four hours.

Once on the barren ridge above the tree line, it had just been a matter of a long slog, ever-upward, for another 2,000 vertical feet. The scenery off both sides of the hogback ridge was fabulous, and by noon we were “on top of the world,” and striking out across the grassy flattop toward a viewpoint knob I remembered from 1986. It looked right down into the bottom of the deep canyon where the Creyke brothers always set up camp, and it offered us a superb location both for glassing and for pitching our own tent.

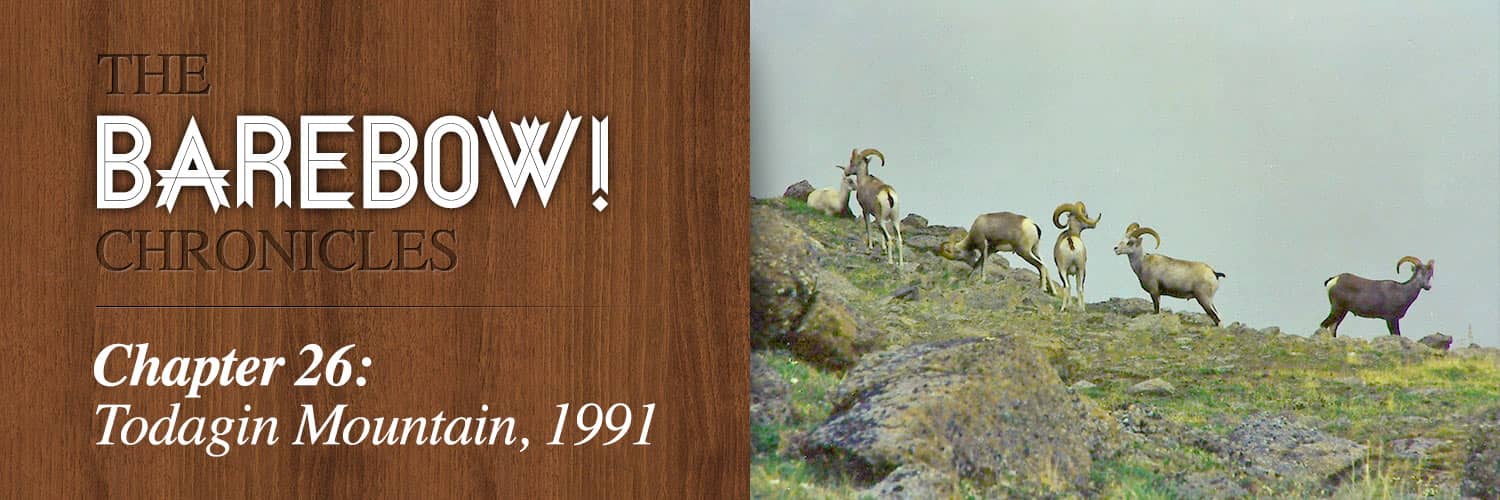

The following morning was the day before the season opener. We started breakfast off with a couple of freeze-dried dinners and then we shouldered our daypacks and started hiking “inland” in the direction of Todagin’s actual summit. Sometime in the late morning, we spied a dandy bunch of rams no more than a mile straight ahead of us. It didn’t appear they had seen us yet, and the physical contours between our position and theirs really provided substantial stalking cover. When we had finally closed the distance to within 300 yards or so, we set up the spotting scope and began studying the six sets of ram horns. Only one in the band was legal, but he was “super-legal” and possessed a truly mouthwatering set of horns that had to be nearly full-curl-and-a-quarter. He was unquestionably the leader of the band, but he was so old his coat had gradually turned (over 11 or 12 years) to a light, almost-taffy-yellow shade. I could not recall ever seeing a Stone ram with such light-colored pelage. Our challenge now was to keep track of him, if possible, until the light of morning made him legal! This was the kind of ram sheep hunters’ dreams are made of—the kind you never really expect to see, save in your sleep.

Being careful to keep the wind in our favor, Martin and I circled around to get above them, hoping to obtain some good pictures without giving ourselves away. When we reached a point where we knew they were less than 100 yards from us, we stopped to consider our options. I finally decided it was worth risking a move from one bit of cover to a better one, some 20 yards distant. What I didn’t know was that they had stopped feeding and were now on the move themselves. We had not transited more than half the yardage necessary when suddenly the patriarch burst into view not 30 yards away! Martin and I were caught right out in the open, without even time to drop to the ground. The jig was up! I watched the eyes of the lead ram grow big as saucers, before hooves went flying, and all six sets of horns set sail on the whirlwind for the ravine down below that eventually funneled into the deep gorge that the Creykes used for their base camp.

I doubt those rams stopped running for at least three miles. Along their escape route, we did catch a glimpse or two of them, but I don’t think they really slowed their pace much until they reached the deep hole where the outfitter would soon be arriving to set up camp with his hunters. After crossing the creek, the band of fugitives seemed to regain its composure, and they soon began feeding their way up the left-hand side of the canyon, toward the knob where we had pitched our tent the evening before.

As things turned out, we did find them again just as night was falling. Two additional rams had joined the group. They were only 400 yards from our tent, milling around at the base of an 80-foot, vertical precipice. The Ancient One was right in the middle of the other seven, and he was the only one already bedded for the night.

The time was pushing 10:30 p.m., and the pictures I was able to take with my still-camera did not have the benefit of the best lighting. As we retired for the night, we prayed the rams would still be there waiting for us at first legal light. If Mr. Super Ram were still in the same bed where we’d left him, we had little doubt we could humanely save him the trouble of ever getting up for another day. Our plan was simple. From almost straight above him, we would both release an arrow at virtually the same instant. A drawing of straws determined that Martin would hold off on making his release until he heard mine. Were I to miss, then the ram would be his.

A few hours later, when the half-light of the pre-dawn wormed its way under our eyelids, our internal alarm-clocks went off, and we peeked outside the tent to see what sort of weather we might be dealing with on opening morning. Imagine our shock, as the first thing our vision encountered was a band of eight rams only 200 yards away, right out in the middle of a broad, grassy plain as flat as a pool table! Yes, it was the same eight we had “put to bed” only a few hours earlier. So much for shooting the big boy in his bed!

The eightsome appeared to be slowly feeding off in a southerly direction. Not willing to give up on our dream of arrowing their leader, we decided to follow them at a substantial distance and see if they might eventually make themselves vulnerable to a feasible stalk. Unfortunately, that just never happened, though we did manage to keep them in view for several more hours.

The next few days didn’t produce any better luck for us than had opening day. From time to time, we would spot in the distance the outfitter’s hunting party, but we never crossed paths with them until we decided early one morning to head due north from our tent. That decision meant dropping all the way down into their camp and climbing up the steep horse-trail on the other side. They were startled to see us, and I was surprised to recognize Stan Godfrey, an excellent bowhunter from Wisconsin, whom I had come to know a bit from attending several Pope and Young conventions. Later that day, he was to arrow a very nice Pope and Young ram—which we would discover on our way back through their campsite that evening. Stan was kind enough to give us a nice piece of fresh meat from his kill. It sure did put our freeze-dried menu to shame, once we finally made it back up the hill to our tent.

With only three days left to go for our hunt, Martin took a fall in the rocks, and it broke some crucial piece of metal on his compound bow’s arrow rest or bow sight. He knew he had a replacement piece down at the bottom of the mountain in my Subaru, however, so he made the tough choice to spend most of one day making that demanding round trip. Otherwise, he felt his hunting was finished. Consequently, I was on my own for the day, and I headed northeasterly into an area we hadn’t yet explored.

By mid-morning, I was into sheep—lots of them. Maybe as many as 75 or 80! Most were females and juveniles, but, much to my surprise, I found one very nice, mature, legal ram hiding out in the midst of them. At that time of year, most self-respecting rams are hanging out in bachelor groups and don’t want to have anything to do with the ewes and lambs. The handsome ram was probably using them for “cover,” I assumed. As the herd traveled, I stayed well behind, but eventually the big fellow joined up with two junior rams, and the three of them split off from the rest.

Some contours in the plateau there offered me an opportunity to circle and get ahead of the trio, although I knew I would have to hustle. Fortunately, the three rams bedded within a half hour, and I found I was able to start moving straight in on their bedded location by placing a solitary, earthen “haystack” directly between me and them. This was a truly bizarre, dirt-and-rock formation that stood around eight feet tall by six feet wide, right out in the open—with absolutely no other geologic anomalies within hundreds of yards in any direction. I had no trouble reaching the pedestal formation sight-unseen, but the rams were lying 60 yards the other side of it, so I was hung up without a single blade of additional cover.

Thus the long hours of the hot afternoon slipped by, with nothing moving—neither the hunter nor the hunted. As evening approached, I began to contemplate the possibility of spending the night there, if the rams did not make a move before dark. Though without a sleeping bag, I did have a fair amount of extra clothing with me. I realized it might possibly freeze overnight, but I started thinking about how I might wrap my booted feet up inside my daypack to protect them from frostbite.

My reverie was brought to an abrupt halt when I noticed the three rams rising quickly from their beds. I peered a bit further around my cover, only to feel my heart drop into my gut as I saw another bowhunter coming into view a hundred yards away. As the rams took flight, I stood up in disgust, cursing under my breath. If only my quarry had risen and fed innocently in my direction before the intruder had come along! He’d seen them from a distance and had been trying to put the sneak on them. He had been too careless with regard to the wind, however, and that had ended things for both of us. When he noticed me standing next to my “haystack,” he hiked over and apologized profusely. I could tell he was sincere, so I thanked him for his apology, and the two of us went our separate ways.

Martin had dinner ready when I finally poked my smiling, hungry visage through the tent door, as the last vestiges of a stunning sunset were being swallowed up by the fall of night. He’d been able to fix his bow, yet in the end it was not to make any difference. We hunted hard the final two days, probably averaging 12 to 15 miles per day. We only saw two rams during those last 48 hours that might have been legal but weren’t able to get close enough to either one even to worry about making a decision as to legality.

The scenery had been spectacular (as always, in sheep country), the weather superb (even too hot, much of the time), and the adventure had certainly offered us a few moments of excitement which only whetted my personal appetite for another effort—in another season. As Martin and I hiked off that mountain the evening before our long drive back to Vancouver, I realized the denial of victory on that hunt had only made my resolve even stronger—to get within a stone’s throw of a Stone ram, one day—and then to harvest him with my bow.

Editor’s note: This article is the twenty-sixth of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the twenty-fifth Chronicle here.

Top image by Bryant Dunn