The BAREBOW! Chronicles: The Nevada Lottery-draw Tag, Part 1

Dennis Dunn 03.17.15

No hunter can hope to claim the North American Super Slam without also taking the Grand Slam of the continent’s four species of wild sheep. Undoubtedly—for a bowhunter, at least—the Grand Slam is the toughest part of the Super Slam to achieve. After the sheep, for a close next-most-difficult, my nominee would be the grizzly bear, which I had to hunt seven different times before my efforts were at last rewarded with success.

Since the Grand Slam is an integral part of the Super Slam, the reader will understand how excited I was in the spring of 1999 when Nevada outfitter Mike Hornbarger called me out of the blue to inform me I’d just received a desert bighorn tag on the annual Nevada lottery-draw. I’d been fortunate enough to harvest my Dall, Stone, and Rocky Mountain bighorn in 1984, 1993, and 1994, respectively, so the news convinced me all over again that I am absolutely the luckiest man I’ve ever met.

It was my eighth year of applying for the tag, and when I learned I’d been drawn, I realized instantly that this hunt was going to be the most important one of my life. No Grand Slam, no Super Slam! The extent of my good fortune becomes evident when one considers that 163 nonresidents had applied for the single nonresident tag available that year in the Game Management Unit (GMU) known as the Stillwater Mountains, in north-central Nevada. Mike Hornbarger had called me to offer the outfitting/guiding services he figured I would probably want when the season opened in mid-November. He guessed right, of course, and the negotiations began immediately.

***

The Stillwater GMU runs pretty much north-south and is well over 100 miles long. Since it averages about 10 miles wide, the sheep population of around 150 has a lot of room in which to spread out—like eight or nine square miles per animal! Fortunately, however, sheep tend to be herd animals and travel in groups, making them a bit easier to spot from far away. Yet the pelage of desert sheep matches exceedingly well the color of their rocky, arid environs and gives them an exceptional coat of camouflage that often defies detection—unless, perhaps, the animals are on the move. Because sheep are inclined to bunch up, hunting the Stillwater’s relatively sparse population presents a particularly difficult challenge to the bowhunter. With only one band of sheep to be found in as much as 40 or 50 square miles, finding any at all is the first hurdle. Then, once you’ve finally located a group containing a mature ram, stalking to within bow-range of such an animal becomes the supreme challenge in all of North American bowhunting.

This may sound crazy, but the only sensible way to hunt the Stillwater Range for desert sheep is to remain in your vehicle until you find the ram you want to go after. Some explanation is in order. The top of the mountain range and most of its western slope are covered with trees. The eastern side of the range, however, is steeper, more rugged, and almost entirely devoid of trees. For these reasons, and also because there are so many coyotes and mountain lions in the region, the sheep population hangs out virtually full-time on the open eastern slopes. Above all else, they depend on their superb eyesight for survival. With no forest around, it is far more difficult for any predator to ambush them successfully.

Now then, luckily for the human sheep hunter, there is a 100-mile-long dirt road that parallels (at very close range) the bottom edge of the Stillwaters’ eastern flank. All vehicular traffic travels that one road only, and every sheep in the high country watches that road like a hawk. They all know that man, the predator, can access their mountain haunts only on foot, and primarily from that one road. Before I ever flew down to Reno for this hunt, Hornbarger had set up a very comfortable camp at the base of the range’s midpoint. Every morning during the hunt, the routine would be the same. Gary and I would start driving that road at first light, with his spotting scope attached to his roll-down driver’s window. Every 100 or 200 yards along the way, we’d pull over, kill the engine, and systematically glass the rugged mountain ridges and canyons above us. Though we might have to travel 20 miles in one direction or 30 in the other, sooner or later, on nearly every day, we would find sheep somewhere—maybe a mile above us, maybe three or four miles back into the range. Without exception, every single time we found sheep, we found them looking at us also!

The only way we had any chance of making a stalk on a group of sheep (after one was located) was to continue driving down the road until some intervening ridge blocked us from their view. If we could no longer see them, they could no longer see us, and it was then safe to turn our Jeep off the road in the direction of the first foothill that could give us access to the high country. Even when somebody would park on the edge of the road, open a car door, and start walking in the direction of the mountain range, without fail any visible band of sheep would start running farther into the backcountry—even if they were already 3,000 feet above the road and two miles away! I had never witnessed such spooky animals in my life!

The 1999 Nevada desert sheep season opened on November 13, and my guide had spent several days scouting the range from the road before I ever arrived in camp. Gary Coleman has a burning desire to see each hunter succeed, and his motto is “Whatever it takes!” However, not knowing what a great guide he would turn out to be, I offered him some extra incentive. After explaining why the harvest of a desert ram was so terribly important to me, I said, “Gary, if we’re successful together in this enterprise, I’ll treat you to an Alaska caribou hunt as my guest!” His eyes lit up momentarily, for sure, but I imagine he’d heard other such promises before and didn’t accord them a whole lot of credence. He didn’t yet know me very well, either.

On the hunt’s first morning, it didn’t take Gary long to locate a band of sheep he’d been keeping an eye on. After being careful to continue driving forward till they were completely out of sight, we shouldered our daypacks and headed across the sagebrush flats to the base of the range that lay only 200 yards away. That first day’s climb involved no more than 2,500 vertical feet, but the altitude gain was plenty enough for me—given the fact that I had just come from sea level to a valley floor where our starting point each day would always be at least a mile high. Once we reached our target elevation and peeked over the ridge-crest, the sheep we expected to see below us were nowhere around. We searched for them till nearly sundown and completed our descent back to the truck long after dark.

The above scenario replayed itself over the next 10 days. Sometimes Gary and I would manage to relocate the target group of sheep after our long climb, only to have the wind change direction on us before we could complete the final hundred yards of our ambush plan. Alternatively, one of them would spot us at just the wrong moment while we were partially exposed for a second or two. Or else one of us would dislodge a small rock accidentally, which would alert them to the presence of intruders as it proceeded to tumble down the mountainside.

I shall never forget the thirteenth day of the hunt, because that was the day which provided me my first opportunity to harvest a desert ram. As so often happened, the sheep we’d expended three hours of sweat over were nowhere to be found when we finally arrived at the place we had last seen them. The east side of the range is laced with a labyrinthine maze of steep canyons, almost none of which can be followed either up or down on foot because of numerous dry, vertical “waterfalls” that hang you up and prevent further progress. As if with the wave of a magic wand, our sheep that day had simply disappeared into some hidden little arroyo pocket. The only sensible plan was to position ourselves on top of a nearby, elevated vantage point and patiently await their reappearance.

By 1 p.m., the midday sun was becoming more than warm. Gary and I had been fighting the drowsies for a good hour or so, and had lain down amid some sagebrush about 90 yards from a rounded rock-dome where we’d previously seen sheep milling around from the valley below. As we tried to take turns napping, we positioned our heads in such a way that, without having to lift them, we could still keep an eye on the barren knob. I have no idea how much sleeping actually took place, but I recall suddenly opening my eyes to the sight of a ewe profiling herself against the sky right on top of the dome. Her approach had been invisible to us. Suddenly, they were simply there! One by one, 15 more sheep followed the lead ewe right over the top and down the precipitous side-hill out of sight.

“Gary!” I whispered, as the first sheep image registered in my brain. “We’ve got company!”

“I know,” was the response. “Don’t move a muscle till the last one disappears.”

They had arrived from below, off to our left. When the last of the 16 vanished from view off the very steep right side of the knob, Gary jumped to his feet, shouting at me (in a whisper), “Let’s go! Run as fast as you can, and nock an arrow!” Within seconds, we were on top of the dome, peeking over the edge to see what was below. There they were! All of them, just standing in the shadows at a good 60-degree angle straight underneath us. As I drew my bow and took aim at the broadside, standing ram which was obviously the band’s patriarch, Gary (using the rangefinder he had pulled out of his pocket during our run) whispered, “90 yards.” Unfortunately, I was forced to let down my first draw, because I was afraid of hitting one of the ewes that surrounded the big ram. Then, suddenly, he was standing all alone in the clear, as the stunned lookout ewes began to depart. Within another second or two, my arrow was away. The shot looked true until the last instant, when it passed just over the middle of the ram’s back. His binos trained on my target, Gary told me later he didn’t think I’d missed by more than a few inches.

The downhill angle of the shot had been so severe that I’d overestimated the amount of arc my arrow needed to trace. Had I made the shot as if it were 50 yards on flat terrain, I’m sure I’d have scored a fatal hit. I had adjusted some for the steep angle—but not enough! Hindsight, naturally, is always perfect. Ten minutes later, we caught a glimpse of the sheep still running several miles away.

Obviously, after 13 days of hunting, I was terribly disappointed at having blown my first great chance at a desert ram, yet I also felt elated—just for having had the opportunity at all. Had I been hunting with a rifle, I knew, this very fine animal would have been mine, and I guess I found a certain modest consolation in that. Besides, day 13 was November 25, Thanksgiving Day, and I knew enough to be grateful for all my many blessings—including the blown shot opportunity and the great turkey dinner that Sherry Hornbarger had waiting for us when we finally dragged ourselves back into camp that night.

The fourteenth day we took off for total rest and relaxation. Only 15 miles from our camp were some natural hot-spring pools which proved a welcome balm for our tired muscles. It was also a day for pigging out on Thanksgiving leftovers! With batteries recharged, Gary and I tackled the second half of the month-long season with renewed determination.

About 20 miles south of our basecamp lay Mississippi Peak, one of the tallest and biggest mountains in the Stillwater Range. Knowing there were sheep up in the high country there, we decided to pack a spike-camp several miles up the main access ridge to not far below the summit, and then hunt down on whatever rams we might find underneath us. We loaded our gear and enough food for three days into our backpacks, and—shortly after daybreak on day 15—we began the long, gut-wrenching, four-hour climb. The elevation gain must have been nearly 4,000 feet.

Well before my arrival for the start of the hunt, Mike had gone to considerable effort to construct and paint a rather nifty cardboard decoy that represented the rear view of a desert bighorn ewe. The lightweight decoy consisted of two pieces, hinged together, with the part that swung upward showing the ewe’s neck and head, while the lower section showed the ewe’s big rear end (and partial hind legs) at about twice normal size. If used in the right manner, at the right time and place, Mike thought it had a good chance of attracting any ram that might be suffering from testosterone overload. The various colors on the decoy were very accurately painted, and the wooden handle glued to the back side of the larger section made carrying it around (in collapsed position) very easy.

Gary and I didn’t carry the decoy with us every single day, but we did quite often, and we certainly wanted to have it with us on our three-day spike-out in the high country of Mississippi Peak. In the course of this little adventure within the larger one, we did manage to locate several very nice rams—one of which we tried using the decoy on, to lure him within bow range. With considerable patience and caution, we crept eventually to within 150 yards of our quarry. When we set up our decoy in between some bushes on top of a mound of sandy soil, it got the ram’s attention instantly. He stood there for several minutes staring at it, and then just as he began his first steps in our direction, a wayward gust of wind came out of nowhere from behind us and knocked the cardboard sham forward onto its big, fat you-know-what! Talk about “spooked!” That ram (and his whole flock of sycophants) changed counties so fast, they left Gary and me rolling on the ground in laughter. Albeit with humor, the wind had once again sabotaged our best-laid plans.

By way of the starkest contrast possible, the following day produced a sheep encounter that left both Gary and me shaking our heads in disbelief. In the late afternoon, we found another good-sized group of sheep that contained one dandy ram in the high 150-class. They were feeding in a large basin below us, at the upper end of which was a saddle between two ridges. Right in the middle of the saddle was an old, bushy juniper tree. Gary directed me to go down and around on a route that would bring me back up to the saddle from behind, and then to hide myself in the juniper. Once I was in position, he would circle down and around in the other direction, enter the basin well below the sheep, and then see if he couldn’t drive them up to the saddle—where I’d be lying in ambush.

Well, the plan sounded good, but an hour-and-a-half later Gary arrived from below at my hiding spot with a truly amazing story to tell. After getting well below the band, he had put himself in full view and begun climbing straight toward the sheep. Most remarkably, they just stood there and watched him come! Evidently, they had never before seen a hunter behave that way, and they continued to watch with ever-increasing incredulity until Gary walked right up to the big ram—stopping, finally, just 10 yards away! Why, oh why, he thought, weren’t our two roles reversed that evening? In discussing the bizarre situation later, we figured that because the evening thermals had changed from uphill to downhill, the sheep had not been able to pick up Gary’s scent. Had they done so, they most certainly would have bolted at first whiff. The other factor may well have been that Gary simply had not been behaving like a predator.

Nothing else seemed to work in our favor, either, during the three days we spent high on the flanks of the big Mississippi. Two other stalks on good rams were also foiled—either by a sudden change of wind direction, or by an unpredictable change in the feeding vector of the sheep. Nightfall of the final day found us back in the big tent at base-camp, enjoying the kind of outstanding gourmutton’s dinner that no spike-camp can produce. At daybreak the next morning, the routine of the traveling, optical “road show” started all over again.

Day 18 was a bust, but day 19 provided enough excitement to make up for the previous five. We started glassing from the road by 7 a.m., and within an hour we had spotted two separate bands of sheep, which soon merged into one larger group of 13, containing five rams in all. We aborted our first attempted stalk and returned to the truck quickly, rather than take a big risk of “blowing them out.” They soon descended almost to the valley floor, whereupon we tried a second stalk—this time successfully getting above them.

After a couple hours of waiting them out, we saw the band start to move back up the bottom of the steep, narrow canyon they were in. We had already crawled through and past all our available cover and were lying prone on the lip of one side of the cut they were traveling. Before long, the sheep were about 70 yards below us, and the time for action was instantly upon us. By the time I could get my feet under me in position to shoot, the nearest ram was at least 80 yards away and had begun climbing the steep canyon wall directly across from me. My first arrow landed between his feet, just a bit short of the mark. Gary then gave me a distance from his rangefinder on a second ram that was already halfway up the far cliff, but had stopped to take a look at what had caused all the hubbub. “Ninety-four yards,” was the word. My second shot seemed to have perfect elevation, but—according to Gary’s observation through his binoculars—the arrow passed about eight inches in front of the ram’s chest.

Finally, my third arrow, fired at yet a different ram even higher up on the face opposite (103 yards, by rangefinder), was a perfect shot (according to Gary), but the stationary ram decided to take two steps forward while the arrow was in flight—resulting in a clean miss! A lot of hurly-burly, a lot of excitement, but no victory. In the space of roughly 30 seconds, I had released three arrows at three different, mature rams, yet had nothing to show for it—save a sad-sack, grimy, grimacing visage that not even a mother could love.

I was beginning to wonder if this physical and psychological ordeal was ever going to come to an end. Eleven out of 19 elapsed days of the hunt had brought me within 300 yards, or less, of a desert ram. How easy with a rifle, I found myself thinking one more time! But with a bow, and without sights? Was I crazy? To Gary Coleman’s enormous credit, I have to stress one point: he kept assuring me every day that we really could get the job done; that our luck would finally change before the long season came to a close. I think Gary had come to believe in me perhaps more than I believed in myself. Or maybe it was just that he believed so much in himself—in his ability to make it all happen for me. Regardless of where his faith may have lain, it proved to be justified. Day 20 was to be our day of destiny!

Editor’s note: This article is the forty-third of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the forty-second Chronicle here.

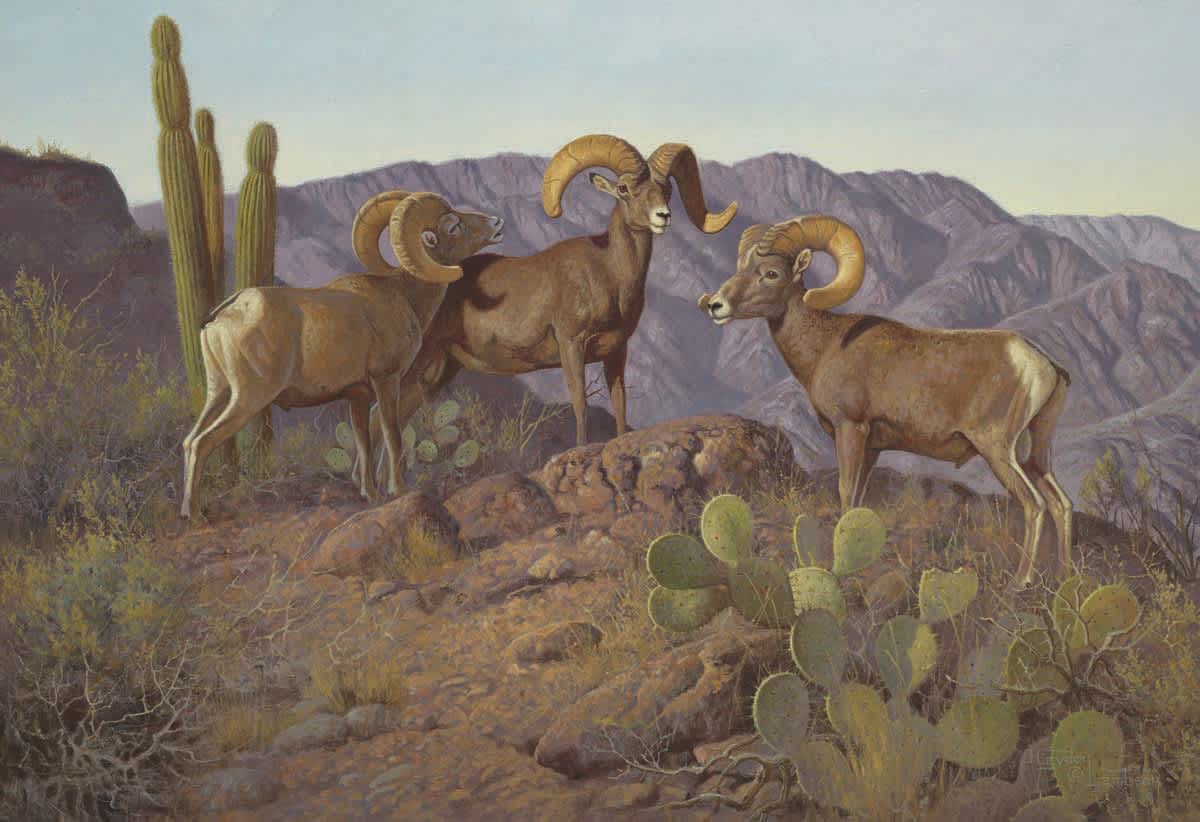

Top illustration by Hayden Lambson