The BAREBOW! Chronicles: This Side of the Horizon

Dennis Dunn 05.15.15

With his eyes glued to his binoculars, my guide’s voice muttered, “Don’t you think you could have found one somewhere on this side of the horizon?” I burst out laughing, as Dan Stobbe now turned to look at me with a grin.

“Damn, that’s a long way from here, Dunn!” Stobbe continued. “I’m not sure he’s not up there in the Northwest Territories! How’d you ever spot him without a spotting scope?”

“I just kept looking for a speck of white anywhere shy of the skyline,” I answered, still amused at his initial question.

Although our binos were not revealing any details of the animal yet, we both knew we were looking at the white cape of a nomadic mountain caribou bull that had wandered into view some five or six miles distant.

The time was late September of 2000; the place was the northwestern edge of the famous Kawdy Plateau in northern British Columbia. This was only my second hunt specifically for mountain caribou. The first one—in 1998, in the Northwest Territories (NWT)—had been unsuccessful. Dan was not only my guide on this hunt, but he was also the owner of Cassiar Stone Outfitters. I had previously hunted moose with his outfit in three different years, but this was the first time I’d ever had the pleasure of his company and personal expertise.

We had been a good fit, it seemed, since we both enjoyed conversation. The hunt was almost over now. In two days, other hunters and guides would be arriving at the cabin we were using, and then the long horseback ride to Tuya Lake would take us back for the scheduled rendezvous with our float-plane. There hadn’t really been much to do during the hunt—other than to sit on top of the highest hill around those parts, glass every so often (till your eyes grew tired), and talk. Judging by the many small, beat-up evergreens in the vicinity of our hilltop, we concluded most of the caribou in the region had already passed through during the preceding three weeks of the season. A number of little trees had been thrashed to within an inch of their lives during the most recent velvet-stripping ritual, but there surely seemed to be very few animals left on or around the fringes of the Kawdy Plateau.

Three times we had used the horses in camp to go after other bulls we’d spotted off in the mega-distance, but the rides had always ended in disappointment for one reason or another, once we got close. In one instance, a dandy bull had somehow broken off one of his main antler beams halfway down from the top. In two other cases, the bulls just didn’t quite meet the definition of “legal” for mountain caribou—as defined in the BC Hunting Regulations booklet. The legal definition required no less than five top points on at least one side of a rack, and “rear points” at least a full inch long. With so few animals now migrating through our area, the challenge had become simply finding a legal bull—any legal bull.

Just as I had done the year before, when I finally harvested my Canada moose, I had flown from Juneau, Alaska, across the border into northern BC. The lake where the pilot landed me was called Kilgour, and it was nearly a day’s ride from the “Half-Camp” cabin out of which I was to hunt caribou. The “trail” along the way was a showcase for some great scenery, and we even enjoyed the additional spice of a chance encounter with a grizzly, as well as a pack of wolves. Dan didn’t quite get his rifle out of its scabbard in time to get a shot off at the fast-departing pack, but it was an education just to see how fast they could run.

Yet now, as I was saying earlier in the story, the hunt was nearly over. The bull I had spotted so far away with the prominent, white mane seemed to be headed obliquely in our direction. Dan suggested we go get our horses, which were saddled and tethered just a hundred yards distant behind a clump of alpine hemlocks, and see if we couldn’t ride fast enough and far enough to intercept the lonesome bull. He obviously was in need of company, and we intended to provide him some.

Between his travel and ours, it took us about an hour to get close enough to where Dan could judge the legality of the bull’s rack. We maneuvered the horses to the base of a little, rocky hillock, then climbed it on foot, before setting up the spotting scope. Our quarry was still a good 700 to 800 yards away, but Dan—from our elevated position above the ubiquitous, six- to seven-foot-tall, black willows—finally gave me the thumbs-up sign, after having one eye glued to the eyepiece of the scope for at least five minutes.

“He’s legal, Dennis, but we’ve got to get a move on. He’s traveling pretty fast, and the wind is wrong for us to make a straight-line intercept. We’re going to have to circle around behind him, then get ahead of him again, and come at him from the other side.”

“Thank God he’s legal!” I said, as we quickly retraced our steps back to the horses. “We’re running out of time.”

Before remounting my horse, I remarked to Dan that I needed to do some quick housekeeping with regard to my shooting equipment. Even though I had had my bow (with its bow-quiver attached) securely zipped inside a scabbard specifically designed for carrying bows on horseback, the previous hour’s journey through persistently-heavy and -recalcitrant brush had managed to pop most of my broadhead arrows out of their respective notches in the bow-quiver. As a result, the arrows were flailing around loose inside the scabbard, back on my steed’s right-rear flank. With action imminent, I knew I needed to put everything back in place in a hurry.

Being seated on our horses gave us just enough visibility over the tops of most of the willows to be able to keep our migratory nomad in view more often than not. After completing the circle behind him and moving out a bit in front, once again, Dan rode to within 70 yards of the narrow, little corridor the bull was following and motioned for me to dismount.

“If you grab your bow and run like hell, straight ahead that-away, you should be able to get there just in time to ambush him at close quarters,” whispered Dan. Unzipping my bow scabbard in a flash, I yanked the bow out of it, noticed with great relief that all the arrows were still in place, and took off running in the direction Dan had pointed me. On the fly, I managed to remove one shaft from the quiver and get it onto my bowstring. I arrived at the edge of the bull’s passageway in the nick of time. Though he was still quartering toward me at 35 yards, I took a couple of deep breaths and came to full draw. In mere seconds, his steady walk brought him fully broadside to me at 22 yards, and I watched my arrow suddenly leave my bow and disappear through the middle of his rib cage. It was over just that quickly! I couldn’t believe the moment of truth had already come and gone.

The bull went crashing straight away from me into the heavy willows and was out of sight in a trice. I knew he would not be on his feet for more than a few seconds. Upon turning to head back toward Dan, I saw him riding toward me, pumping his fist in the air. From his perch in the saddle, he had actually seen my bull go down in the tall willow bushes. Finding him, therefore, was easy, as he lay no more than 80 yards away. My shot had been a total pass-throug h, yet all searching for the arrow proved futile.

h, yet all searching for the arrow proved futile.

Since it was already evening, we were now in a race against the diminishing daylight. My bull with the beautiful white mane did, indeed, turn out to be legal. He was an old one, however—no longer in his prime. His antlers were heavy, but the top points were not long enough to allow him to qualify, quite, for the Pope and Young minimum of 300 points. A year or two earlier in his life, I have no doubt he would have easily exceeded that minimum. In view of how slim the “pickings” had been all week, I was thrilled to be able to harvest him and claim the new species. I also was more than a little grateful to Dan Stobbe, who is one of the finest mountain guides with whom I have ever had the pleasure of hunting.

After field-dressing the big-bodied animal, we left all the meat there for Dan to return and fetch the next day with a pack-horse. To facilitate the relocation of the meat, he tied a series of bright pink lengths of surveyor’s tape on the tops of several tall willows. He was able to tie the head, cape, and horns of my bull to the back of his saddle, across his horse’s broad rear-end—thereby creating the biggest fanny-pack I’d ever seen. Following his horse on my own, all the way back to the cabin that evening, gave me a great sense of inner satisfaction. We arrived just at dark. Thank heaven’s we had not had to ride from the far side of the horizon!

Editor’s note: This article is the forty-seventh of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work, and the various editions of BAREBOW! available, by clicking here: http://www.barebows.com/. You can also follow BAREBOW! on Facebook here.

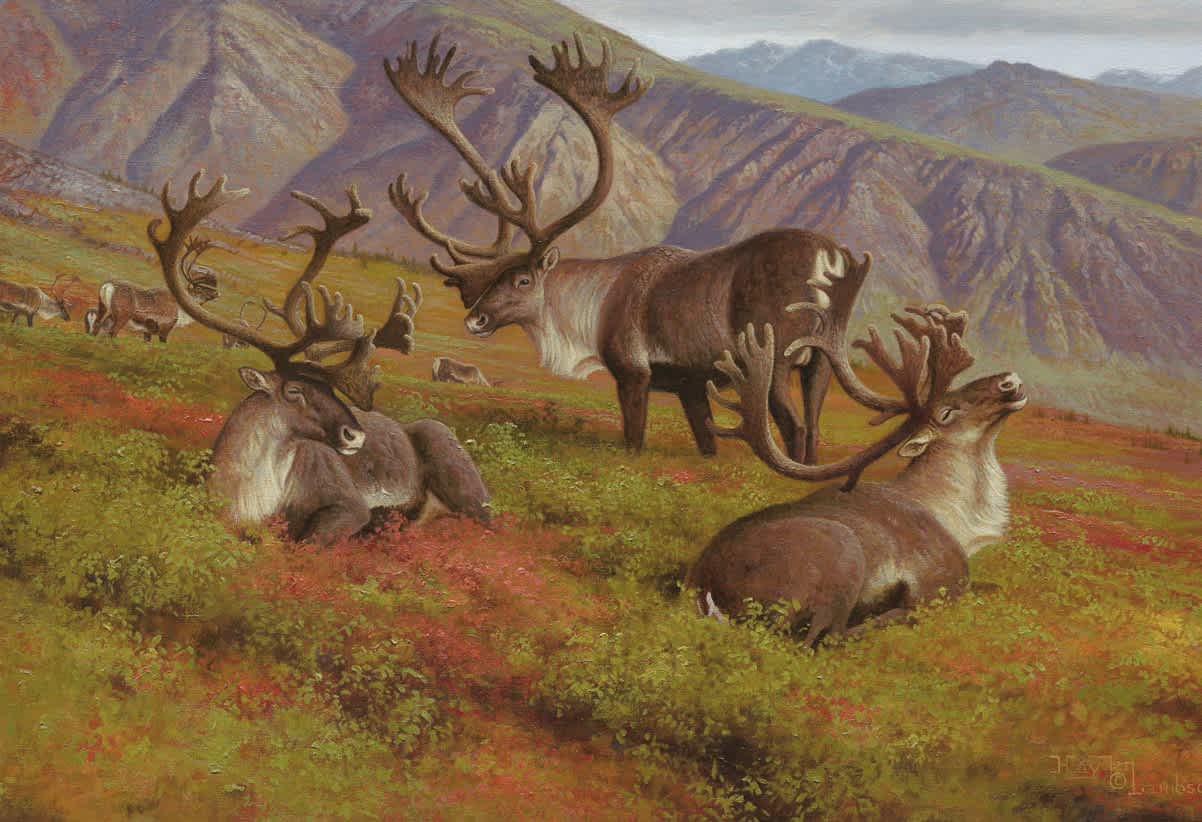

Top illustration by Hayden Lambson