The BAREBOW! Chronicles: When Hell Really Did Freeze Over

Dennis Dunn 07.01.15

There are just some hunts you should never go on! The trouble is you never find that out until it’s too late! I experienced one of those about eight years ago, and it was truly “The Bison Hunt from Hell!” Not that any of it was the fault of MVP Outfitters (Dean, Katy, and Dustin Roe). They were just victims like everybody else.

In late January of 2007, I had booked the hunt by telephone from the SCI Annual Convention in Reno, after learning that the Roes had taken over the hunting lease on the Blueberry Indian lands near Pink Mountain in northern British Columbia. In late 2000, I had taken a bison bull with Mike and Dixie Hammett of Sikanni River Outfitters, but it was not an old bull with sufficiently massive horns to meet the trophy minimum established by the Pope and Young Club. The species is one of seven from the north American Super Slam that I’m still seeking to “upgrade” to Pope and Young quality, before Father Time puts an end to my hunting in this lifetime. Supposedly, the numbers of free-ranging buffalo on the Blueberry Indians’ hunting concession are quite a lot higher than anywhere else, so my second bison hunt was booked with the Roes for the week of November 28 through December 4, 2007. It did not go well.

Even a bad hunt, however, usually has a saving grace or two—if nothing else, in the form of new friendships that are made. This one at least generated some plusses in that ledger! Shortly before the hunt began, I learned from my Wisconsin friend, Mark Zastrow, that he was going to be there in hunting camp with me, and that Dr. Tom Vanasche, of Albany, Oregon, was planning on driving up to Pink Mountain for the same week’s hunt. Since I was also planning on driving up, I called Tom and proposed that we make the trip together. It seemed a natural fit, so he offered his 2005 Chevy Suburban, as it contained much more space inside for bringing home buffalo meat than my 2003 Subaru Outback.

I accepted his kind offer. I warned him that the seasonal temperatures so far north could well get down to 30 below zero, and he assured me he would have his rig properly winterized for those conditions.

Our two-day drive up to the Blueberry Indians’ Lodge was uneventful, and when we arrived late in the afternoon of November 27, the temperature was only a few degrees below zero. The ranch with the lodge on it had been bought by the Blueberry Tribe after BC Wildlife awarded them the hunting concession previously held by the non-Indian outfitter who had built the beautiful lodge for his own home and base of operations. It is a very substantial, spacious, two-story, log home with all modern plumbing and other conveniences—very efficiently heated by two large wood stoves. The upstairs must contain at least six bedrooms and sleep a dozen or more.

In addition to Zastrow, Vanasche, and myself, our group of five bowhunters included Bryce Olson (Texas) and Mark Beeler (Wisconsin). Three of the five of us were there, attempting to realize one of our romantic boyhood dreams with strictly traditional archery gear. The two Marks were the compound-bow hunters. Our coterie proved to be most compatible—skilled at everything but killing bison in extreme winter conditions. Whereas the group of archers who preceded us had gone four for four on bison, the only one of us who scored during our week was Beeler, and that was on the first day. Things went downhill from there. As the arctic cold front consolidated its grip on the area, the temperatures fell lower every 24-hour period—as did our fortunes and our spirits.

The first morning saw a reading of -13 Fahrenheit. The second, -19. The third, -24. That was the day the pipes in the lodge froze, rendering the toilets unusable and depriving us of all running water. Life for the cooks suddenly became much more challenging. By the fifth morning (the last day I hunted) the reading in Tom’s truck at first light was 28 below zero. With the indoor plumbing not functioning, nobody really wanted to use the one outhouse available, which was a good 50 yards away from the lodge. Mind over matter, however, works only so long! Thus everyone would wait till they were desperate to go, and then, after counting noses to make sure the outhouse was not already occupied, you’d make a mad dash for it and try to limit your “exposure” on the excruciating toilet seat to as few seconds as possible. Counting guides and cooks, there were 13 human beings living in that lodge for the week, so the “timing” of one’s use of the facilities was hardly a matter of personal choice.

On our final day at the ranch, it was somewhere around 32 degrees below zero. The 20- to 25-mile-an-hour winds that blew steadily for the last four days of the hunt not only added to the horrific chill factor, but they created a violent updraft in the outhouse. And I do mean, violent! Especially because—on the windward side of the old plywood structure—much of the base just above the frozen ground had long since been eaten away by rodents of one kind or another. Thus, when push came to shove, and doing one’s daily “constitutional” became a necessity, it was sort of like sitting down on top of a miniature Boeing wind tunnel! Indeed, the updraft was so strong and the temperatures so brutally cold that, together, they presented a serious challenge to every sphincter muscle whose owner dared contemplate taking a seat. Sometimes, after using a piece of TP (depending on the strength of the updraft at the moment), you’d seriously wonder if you wanted to risk letting go of it—feeling altogether uncertain as to its next direction of travel.

As far as hopping on a snowmobile and traveling 30 or 40 miles a day in search of buffalo was concerned, you were creating your own 25- to 30-mile-an-hour wind! Now then, if you were also heading right into a prevailing 20- to 25-mile-an-hour natural wind, for a total wind-speed of 50 miles-an-hour in your face, you’re dealing with an excessive wind chill.

All I knew at the time was that my hands, fingers, feet, and toes were not happy campers! Not even hand-warmers inside the arctic gloves I’d used on my two polar bear hunts were able to keep my hands from freezing! On top of the warm headgear I’d brought from home, I wore each day a hard snowmobiler’s helmet with a clear plastic visor that pulled all the way down over my face. Therefore, my head was reasonably well insulated from the extreme cold, but every breath I breathed turned instantly to ice crystals that adhered to the inside of the visor, thereby pretty much completely blinding me. Traveling into the eastern, early-morning sunlight was the worst of all! After four-and-a-half days of it, I decided there were limits as to just how much misery I was willing to force myself to endure. Conditions on both my polar bear hunts had been far more comfortable!

As far as the hunting itself went, the bison had made themselves scarce and very difficult to locate. In the abnormally cold temperatures, they were hunkered down in the thickest pockets of dark timber they could find. Under those conditions, our guides told us, they did very little roaming around or traveling. Consequently, our first challenge was locating a bull, and the second was getting within bow-range in that thick timber without spooking them. Having hunted the species twice now, I must say that I consider wild, free-ranging bison to be amongst the wariest and spookiest of all North American big game animals.

Only once on this hunt did I have a decent stalk opportunity on a trophy bull. In fact, my guide, Brian Glaicar, spotted two such bulls one morning, bedded high on a windswept ridge, well above most of the trees. Our climb through the deep snow and several deadfall areas took us well over an hour, and we finally closed to within about 60 yards of our quarry. Once I thought I had the strong wind figured out, I left Brian behind and tried to negotiate the last 40 difficult yards on my own. Alas! It just wasn’t meant to be that day. The swirling wind suddenly did an about-face, and the bulls simultaneously jumped to their feet and took off running, without even trying to locate the critter that had just offended their olfactory organs. Such is hunting. Particularly bowhunting.

It was actually on the first morning of our long drive home that Tom and I experienced our coldest temperatures of all. As we were leaving Dawson Creek and heading for Chetwynd in the predawn darkness, the outside temperature gauge in his rear-view mirror registered a stunning -36 F. Within minutes, our engine started overheating, and the warning messages on the dash panel persuaded us to pull over to the side of the road and let the engine cool down. After reading everything we could find on the subject in the Owner’s Manual, Tom nursed the vehicle all the way into Chetwynd at about 30 miles-an-hour. Once we found an auto shop that could squeeze us into their overcrowded work-schedule, the antifreeze reservoir was then drained and refilled with a more concentrated level of coolant. Back on the road headed south again, we started counting the hours until the outside temperature finally got back up to zero. Then, the following day, the betting was on as to where we would be on the road home when the temperature at long last rose above freezing.

Neither of us had ever experienced such cold. We learned that Hell itself can, and does, freeze over. We may try to hunt bison at Pink Mountain again some year, but it will probably be a few weeks earlier in the season, when the weather is more likely to be fit for both beast and man. As for this hunt, Tom did venture forth all seven days, but I “wimped out” by staying in the lodge, next the big wood stoves, for the final two. I guess there are sometimes when it’s just saner to admit to being a “wuss.”

Editor’s note: This article is the fiftieth of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work, and the various editions of BAREBOW! available, by clicking here: http://www.barebows.com/. You can also follow BAREBOW! on Facebook here.

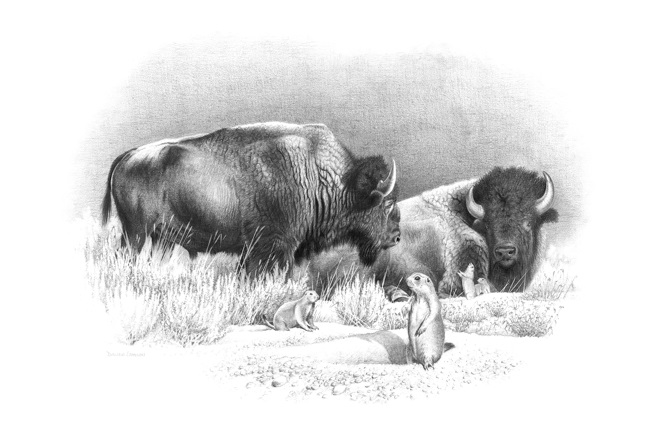

Top illustration by Hayden Lambson