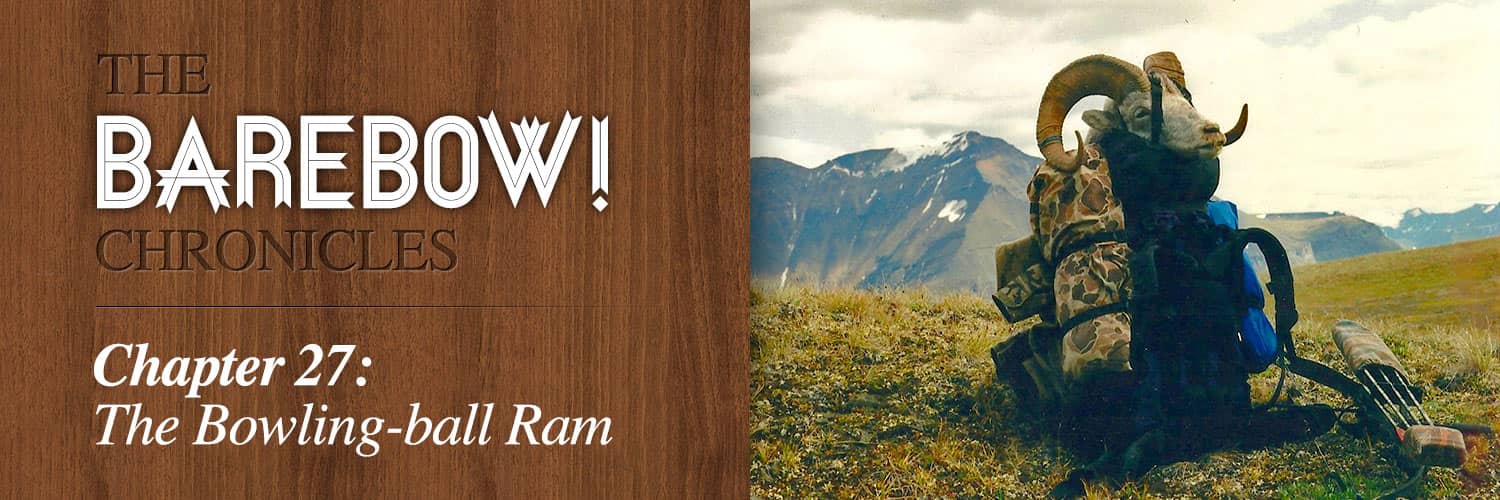

The BAREBOW! Chronicles: The Bowling-ball Ram

Dennis Dunn 07.18.14

After two unsuccessful hunts on Todagin Mountain (one as a nonresident in 1986 and one as a resident in 1991) I was convinced I finally understood the terrain and the habits of the local Stone sheep population well enough to be able, with a bit of luck, to outsmart one of the many resident rams. The real challenge, as always, was going to be finding and outsmarting a legal ram. There were plenty of barely-sub-legal rams around, but finding and identifying a legal one had always been the difficulty on Todagin Mountain. This meant either eight years of age, or having horns that met the BC definition of “full curl.”

The latter definition of “legal” had for years been beset with enforcement problems in British Columbia, and the definition of “full curl” presented in the BC Hunting Regulations had changed several times over the years. Further confusing the picture for the unwary hunter was the fact that the definition in the pamphlet for “full curl” thinhorn sheep was quite different from the definition for “full curl” bighorn sheep. And, as if that were not bad enough, the definition of “full curl” upon which BC Wildlife Conservation Officers based their confiscation decisions was not the one in the annually-published Hunting Synopsis. It was the one in the BC Wildlife Act, as passed years earlier by the Provincial Parliament, and that definition (for thinhorn sheep) was substantially different from the one printed in the Synopsis.

If you are sensing something ominous on the horizon, congratulate yourself on your intuitional perspicacity! This is the story of how I finally managed to take my Stone ram, but it was a harvest that sowed the seeds for 11 years of heartache, frustration, and great personal stress.

My kill on the fifth day of the 1993 thinhorn sheep season marked the beginning of a saga that is almost unbelievable—one that dragged on until finally, in November of 2004, Justice pulled her chin up off her chest and raised her beautiful face to greet me with a smile. The saga is really too long to recount all in one story, so anyone wishing to take in the whole lengthy drama will need to purchase a print copy of BAREBOW!, or Volume IV of my eBook series.

My return to Todagin Mountain was not in the cards until 1993. I had spent two full years developing my game plan. Hardly a week went by that I hadn’t spent some time thinking about the short, “secret” little waterfall I’d found two years earlier. It lay hidden in the bowels of the enormous, south-facing basin which had eroded away the southwestern edge of the high mountain plateau. It came out of nowhere, tumbled down a steep shale slope for 50 feet, then disappeared beneath the rocks—never to resurface again. By no means was it a cataract, but rather a gentle cascade, invisible from anywhere else on the mountain. The soft pitter-patter of its spray was no more than a whisper from 10 yards distant. It was the well-used sheep trails leading to and from this veritable fountain of life that had given away one of the mountain’s best-kept secrets.

Depending on the previous winter’s snow pack, finding water in the late summer/fall on the upper parts of Todagin can be a difficult proposition. The discovery of the “secret” waterfall had fueled my imagination continuously for two years. Any animal traversing the basin at that elevation would be bound to stop there for a drink. As far as I could tell, during any dry end-of-summer, it was very likely the only water anywhere nearby.

I had also noticed in 1991 that there was simply no way to enter this very broad, deep, and steeply-inclined basin without being spotted by any sheep already contained therein. The skyline silhouette of the basin’s long, high outer arms made any clandestine entry impossible. Approaches from below or above were equally infeasible. If I were to have any chance of ambushing a ram there, I was convinced I would have to enter that basin at the start of the season and hide out there—for days, perhaps—until a legal ram came a-calling. If I could stay hidden, it would be just a matter of time before I was bound to have my opportunity. When pressured by other hunters up on the high plateau, the rams would often take refuge in the huge, concave basin—feeling more secure there, and being virtually unapproachable.

***

My 1993 strategy was pretty straightforward. After negotiating an agreement with the rancher, and concealing my Subaru in a shady spot near the base of the mountain, I prepared my internal-frame pack for the challenging 3,500-foot climb up to the top of Todagin’s southwestern summit. I carried with me enough food for eight days, two small tents, a sleeping bag, air mattress, cook stove, spotting scope, tripod, movie camera, toiletries, extra clothing, raingear, and survival gear. All in all, I figured my backpack weighed about 65 pounds. That didn’t count, however, the weight of my bow, quiver, arrows, binoculars, and still-camera, all of which I intended to hand-carry or wear around my neck. Solo backpack hunting does impose additional burdens on the wilderness adventurer.

I began the climb around 2 p.m., knowing it would take me till sunset to reach the “Citadel” up top. The weather was bluebird! Once I exited the last of the trees into the alpine, my spirits began to soar. This was the first solo hunt I had ever made for wild mountain sheep. For reasons hard to explain, I was thrilled to be there on that mountain all alone. For me, the alpine has always been a halfway house to Heaven. In good weather, there is nowhere more beautiful. In bad weather, there can be no place more ugly—or more dangerous. Sometimes, on good-weather days in the alpine, when I am feeling especially close to God, I really don’t want to share that special intimacy with anybody else. Somehow, at such moments, it seems that the presence of a second person puts automatic limits on the extent to which you can feel “at one” with the natural world that surrounds you.

I finally reached the summit of the long ridge as the sun began to snug itself down into the western horizon. I had all but exhausted my water supply, having saved only enough to wet the contents of one freeze-dried dinner pouch. Fortunately, I did manage to locate a tiny, residual snow patch not far from where I pitched my tent for the first night.

Although the location I chose for the larger of my two tents was on the mountaintop plateau, it wasn’t more than 150 yards from the edge of the big basin, as well as the access chute which would allow me easy entry down into that basin. I pitched the first tent inside the deep cleavage of a narrow little washboard-cut, formed by two grassy, rib-like ridges that stood barely 10 yards apart. This tent was to be my refuge in case any major storm-front came in, and it could contain me and all my gear if such became necessary.

My second “tent” was just a tiny bivouac-bag that was seven feet long, barely wider than my shoulders, and 24 inches tall at the head. Barring nasty weather, this was where I intended to sleep for the next week. The bivvy-tent would fit lengthwise on any decent sheep-trail. Many trails crossing from one side of the enormous bowl to the other were not only more-or-less flat, but also wide enough in places to accommodate my shoulders. The more serious challenge was not going to be finding a spot to sleep, but to keep from rolling over in my sleep!

On the morning before the season opened, the sun rose bright and early, and I tried to follow suit. The hard climb of the day before had left my shoulders sore and turned my legs to hamburger. However, within minutes of achieving verticality, a cup of hot cider combined with the sapphire weather to put me “on top of the world.” In the valley far below, a heavy fog-blanket completely obscured the Todagin River draining the lake of the same name many miles to the east. I was looking forward, after breakfast, to taking up residence in “The Big Basin of the Little Waterfall.” If there were any rams already there, I knew that descending the entry chute mentioned earlier would be sort of like trying to reach the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier without being spotted by those guarding it. The biggest difference would be that the Stone soldiers on Todagin are genuinely possessed of eight-power binocular vision.

As it happened, my descent did, indeed, blow seven rams out of the two-mile-wide bowl, but I did not wait for their total disappearance before completing my climb down to the level of the tiny waterfall. Approximately 100 yards west of there was another gully of a totally different character. Instead of being filled with just rock, it was a verdant ribbon of mosses and sods, cutting straight down the mountainside, almost reaching timberline.

I had realized, in studying the topography there in 1991, that—once ensconced within the confines of this narrow little cut—I would be able to move up or down the bottom of the gully freely, without being visible to any sheep approaching the waterfall from either the east or the west. In other words, I would be able to adjust my elevation to match that of any legal ram traversing the basin from one arm to the other. This was the key to the strategy I had spent two years evolving in my mind.

The green gully topped out right at the midpoint of a broad, flat bench which crossed the upper third of “Big Basin.” On the outer edge of that bench, nearly overhanging the precise start of the cut, was one huge boulder I also considered pivotal to the eventual success of my mission. For most of the day, it offered shade from the sun (and shadows to hide in), and its location yielded a splendid view of the entire basin. I knew that by spending all day under that rock, I’d be able to see any ram coming my way from virtually any direction. If a legal ram were to descend the chute from above and behind me, I would hear him coming.

Staying put in that key spot would, indeed, eventually yield me victory. During my two previous visits to Todagin, I’d learned many times over that the sine qua non of bowhunting Stone sheep successfully is to see your quarry (and any companions) before they see you. Yet eyeball versus eyeball, the competition is anything but an even match. Out in the open, well above the tree line, motion is your best friend or your worst enemy—depending on who’s doing the moving. The way I had things figured, once a ram came off either skyline ridge and dropped down into the many hidden folds of the basin’s interior, I would be able to choose the right moment to slip into my green gully from underneath my boulder, and then hustle downhill to whatever altitude seemed appropriate for the interception of my quarry at close range.

Opening morning arrived with the same brilliance and stunning alpine vistas as had the previous day. This time, however, I was in the basin—having spent the night on a sheep-trail in my bivvy-sac, some 200 yards below the lookout-boulder. Psychologically, I was really primed, and in a murderous mood (for any legal ram). “Third time’s the charm!” I said to myself, as I climbed back up to the top of the gully, where I would be spending the next 14 hours.

The hunt did, in fact, prove to be a matter of patience. Days one through four of the season were pretty much the same: perfect weather, lots of sheep coming and going, but no rams that were clearly legal. It seemed that about two-thirds of the ungulate visitors to the basin were making their crossing at the level of the well-hidden water source. The rest were passing higher up or lower down.

Day five dawned like all the others with cloudless skies, and the hope of excitement coming from beyond my horizons. It was to be an extraordinary day I would never forget. Sometime around 1:00 p.m., a very nice-looking ram entered the basin from the east and soon adjusted his elevation to that of the waterfall. While he was temporarily out of sight, I slipped into Green Gully and within minutes had relocated to a spot within the cut just above the well-worn trail that came directly from the falls. He took his time getting there, but after an hour the ram suddenly materialized on the rocky shoulder of the waterfall gully. From where I was situated, the short cascade was hidden within its own cut, but (following a long drink) the ram reappeared and bedded in full view just a few yards beyond the falls.

It was now time to go to work with my spotting scope. Over the next two hours, my quarry drank twice and rebedded twice more not even 120 yards from where I lay in hiding. Throughout most of that time, I had one eyeball glued to the eyepiece of my scope, trying to determine whether or not the ram was “legal.” By the age-rings, or annuli, on his horns, it seemed unlikely he was eight years old. I could tell he was at least six, yet six wasn’t eight, so I thought I’d better make certain the horns were “full curl.” The language in the 1993 Regulations Synopsis stated that at least one horn-tip needed to rise above the forehead-nose bridge-line, “when viewed from the side.”

“Viewed from the side”—just what did that mean? As I kept studying my quarry through the scope, it occurred to me there were many different side views possible. Did I have to be at the same elevation as the ram? Did his head have to be held exactly level with my view of him? Could his head be tilted one way or the other a bit, without my realizing it? It dawned on me the hunter was being asked to judge a three-dimensional object in a strictly two-dimensional way.

Since all sheep horns had to be presented for inspection within 10 days of harvest, and since I had heard that BC Conservation Officers were notorious for confiscating horns from sheep hunters for even the slightest of pretexts, this was not an issue I dared take lightly. In the Regulations pamphlet, I recalled seeing a rather primitive pictograph of a “legal” thinhorn ram, viewed from the side, whose near horn-tip rose just barely above the forehead-nose bridge. I also remembered noting that the tip still had another 45 degrees of arc to “curl,” before it would have become a geometric full-curl. By that, I mean 360 degrees of arc. In the Queen’s English, did “full curl” not mean full circle? Was there a difference? Did it matter? These, and others, were the many questions I was wrestling with as I continued to scrutinize the horns of my would-be trophy ram.

What I finally was able to determine, after more than two hours of study, was that at least the left horn did (just) complete a 360-degree full circle of rotation, even though the horn-tip—when observed as squarely from the side as I could judge it—seemed to curl over on top just at the requisite bridge-line, but probably not above it. Given the direction of the growth-arc, however, it suddenly hit me that it never was going to crest that forehead-nose bridge, if it didn’t already!

In the end, I finally made the decision to try to take this handsome ram, should he eventually decide to cross the falls and complete his traverse of the basin. The way I figured it, the pictograph in the Regs had to be the official, back-up “bottom line,” for enforcement purposes, if the hunter was not able to present for inspection a ram whose horns had actually completed the growing of a geometric full-curl.

Once I had at last resolved the thorny issue in what I thought was an eminently rational way, I began preparing for the ambush opportunity which I felt was surely in the offing. If the ram were to continue his journey across the basin, he would almost certainly pass right below me at a distance of only 11 or 12 yards. Staying low to the ground in the bottom of my cut, I sneaked down to the trail he would probably be traveling and planted one, big, clear, Vibram-sole boot-print right in the middle of the soft dirt on his pathway. I then crept back up to where I’d just been and positioned my body for the long-anticipated shot.

My biggest worry was how to come to full draw without the ram seeing the motion of the upper limb of my bow. There were no bushes on that hillside more than eight inches high. Even just sitting upright on the edge of my gully, so that I could spot him approaching along the trail, would run the risk of his seeing my silhouette—not to mention my drawing motion! I knew there was no way I could shoot an arrow while lying down, but it did occur to me that perhaps I could draw my bow while lying down, if I simply lay on my back against the steep sidehill. Then, as soon as the ram passed below me and stopped to sniff my boot-track, I could sit up, quickly take aim, and launch the arrow for his rib cage.

The strategy sounded simple, but I knew it was going to take perfect execution. I decided to practice drawing a few times while lying on my back, with the bow horizontal across my pelvis. It was an action which felt extremely awkward. No sooner had I successfully executed several test-draws than I noticed my ram getting up from his bed. He vanished inside the water gully, and I began to hold my breath—arrow on the string. My watch read 4:30 p.m. Some instinct told me that this time he would resume his travel westward.

Suddenly his horns appeared, coming my way—80 yards and closing. With the three middle fingers of my left hand curled tightly around the bowstring, I pressed my head and shoulders as hard as I could against the sod behind me and simply froze. When he was nearly directly below me, I began the awkward draw. As his trail dropped down into my gully and gravity increased his gait a bit, I sat up and took dead aim. The boot-trick worked perfectly, and, when he halted to lower his head for a sniff, my arrow passed noiselessly through his chest. Rather than bolting or fleeing in a panic, the ram simply turned around and started walking slowly back the way he had come. I’m not sure he’d felt a thing; at least he certainly wasn’t acting as if he had.

I knew he was mine and that he couldn’t last more than 60 seconds. Just as he reached the near shoulder of the waterfall gully, I watched in amazement as he toppled out of sight, headfirst, into the void. By the time I could run that 90 yards and get a look down into the long, vertical cut, all I could see was a cloud of dust that extended 1,000 feet down the very steep mountainside. There was no sound, save the spray of the nearby water, and no motion down below. Immediately, I pulled out my binoculars. As the dust settled, I finally made out the lifeless form of my ram. The fall had not killed him; he had died on his feet—just one or two steps too close to the waterfall. Then, like a bowling ball, he had tumbled, end over end, many hundreds of yards down the mountain.

***

In looking at my watch, I realized I still had several hours of daylight, and that I was now in a race against time. After retrieving my rucksack from Green Gully, I started cautiously down Waterfall Gully. Just below where the water vanished for good, the shale became pebbles, and then sand. To my delight, I found I could practically ski downhill on the heels of my boots. As I went flying along on the wings of my excitement and the obliging scree, the sobering thought hit me that maybe my ram had busted a horn during his long, uncontrolled tumble. Fortunately, my worries were unfounded. The horns were intact, and I was one happy camper! What a thrill! At that moment, I was on the highest of Canadian Mountain Highs, yet definitely very low down on the mountain called Todagin. I had a ton of work to do, and my spike camp was a long way above me. Little did I suspect what horrific challenges still awaited me.

The slope where my ram had come to rest was still awfully steep, and working on him with my skinning knife wasn’t exactly easy. It took me nearly an hour to cape him out and get the head and horns removed from the neck. I began to contemplate my options when suddenly a thunderclap secured my instant attention. Glancing up at the top edge of the plateau 2,000 feet above me, I saw several black thunderheads coming my way. It was already pouring up topside, but I didn’t have the impression it would last very long. My pack-frame was at the lookout-boulder, and I knew I would need it to get the meat up the mountain. Given where my wheels were located, taking the meat down the mountain was not an option. I was going to have to climb all the way to my upper tent before dark, carrying my spike camp, as well as the cape, head and horns, and then return in the morning to bone out the meat—only to carry it back up to the top of the plateau, so I could then carry it back down to my Subaru waiting at the ranch.

As I was tying my trophy onto the only loop I had on the outside of my rucksack, another thunderbolt rattled through the ramparts above me, and I looked up to see a wonderful rainbow hanging right over the part of the mountain I now needed to climb. It was beckoning, and I was in a mood to get out of that gully as fast as possible. I had no idea what the weather might do next, but all my raingear and survival gear were way up above me on the mountain.

Immediately I found I had a serious dilemma on my hands. The gully that low down had turned into a kind of half-pipe, with walls as hard as concrete that were vertical, or even overhanging in places. To hike back up the bottom of the cut was well-nigh-impossible due to the degree of incline and the shifting sands underfoot that gave me little to push off against. I simply had to find a way to get out of the chute, but it clearly was not going to be easy. It soon started to rain hard, and I became less and less sanguine about my circumstances.

About 20 yards above me on the left edge of the gully, I noticed a rare clump of alders that had somehow beaten the odds and managed to establish themselves a bit above the general tree line. There appeared to be several stout branches draped over the lip of the gully, so (thinking I might use them to haul myself out of trouble) I progressed upward with great difficulty, to the point where I finally could grasp one of the downward-slanting branches. The question was now whether I could haul myself up over the rim to safety.

Unfortunately, I didn’t seem to have sufficient, brute arm-strength to pull it off. After standing tiptoe on the highest part of the wall on which I could gain purchase, I succeeded in reaching two of the branches, but my hands were still nearly three feet below the wall’s rim. I tried three times to get myself up over the edge, but it was slanting downward and really gave me nothing to grab onto. Having 25 pounds of cape, head, and horns tied on my pack was not helpful either.

On the third attempt, as my arm strength finally gave out, I had to let go. When I hit the ground below with a thud, the concussive force combined with the weight of my load to rip the stitching right out of that one loop on the top of my rucksack. In astonishment and horror, I watched helplessly as my trophy—utilizing the perfect, geometric full-curl of the horns—became an even more efficient bowling ball than the first time. I had used a cord to tie the cape and head into a tight little ball, so this time when it went spinning down the mountainside the only thing that stopped it was a boulder right at timberline. A part of me wanted to laugh at the ridiculous situation, but most of me wanted to cry. My brain tried to refocus on my now-even-more-serious predicament. I didn’t want the predicament to transmogrify into a nightmare.

I had no wish to spend the night on that mountain. It didn’t take me long to figure out that the sanest course of action was to abandon my trophy for the time being, and see if I couldn’t find a way to get back to my spike camp before dark. The time was now pushing 7 p.m. I simply had to pray that, overnight, no grizzly would find any of the parts of my ram strewn up and down the gully.

I suddenly noticed, about 60 yards below on the other side of the chute, what looked like a diagonal rib of extraneous, geologic material that traced a line all the way up the wall to the rim where “freedom” was beckoning. The rib was ever-so-slightly extruded from the host matrix. Was the extrusion enough to provide a series of toeholds that might allow me to work my way right up to the green sod above?

Ten minutes later, I was a free man, and I began scrambling up the mountainside on solid ground that did not give way underfoot. What a joy it was! An hour later I reached my spike camp and quickly loaded everything I had into my big pack. From there, it was about 900 vertical feet up to the big tent on top. At final last light, I collapsed into my tent utterly exhausted.

Fortunately, I’d had enough presence of mind to refill two, one-liter bottles with water at the falls. My body’s state of dehydration absorbed it all long before morning came, and two freeze-dried dinners hardly made a dent in my appetite. If that Thursday had taxed my limits, I knew Friday was likely to be tougher yet.

The morning light came much too soon. After wolfing down another double portion of freeze-dried dinners for breakfast, I made the long descent to the bottom of “Big Basin” to recover my abandoned trophy. That done, the next challenge was to exit the gully again and ascend the slope to a point where I could reenter, in order to retrieve the meat. Because of the slope’s incline, the job of skinning and boning probably took a good two-and-a-half hours. Finally, around 1 p.m., I began my last, long climb up to the mountaintop.

I believe I reached my tent about 5 p.m. An hour later, I had everything taken down, reorganized, compressed to the max, and either carefully stuffed inside my pack, or tied to the outside. My best guess was that the fully-loaded pack probably weighed close to 140 pounds. Never before, and never since (praise the Lord), have I ever had to carry a pack anywhere near that heavy. Getting into it and rising to my feet was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Needless to say, without that precious substance called adrenaline, I never would have made it off the mountain that evening of Friday, August 6. The human body seems to do whatever it truly has to do, when called upon in extremis.

I reached my rig just after sundown. As I aimed it down the dirt road which led to the Stewart-Cassiar Highway, I could hardly contain the jubilation I felt. Was I the first American ever to take a Stone ram with a bow and arrow, on a solo backpack hunt and without even a companion to help in the effort? My hunch is that I may have been.

Was that 1993 sheep hunt the most gratifying hunt of my life? Perhaps so. It certainly has to be right up there! What I didn’t yet realize was the very heavy price I was still going to have to pay for my success in the months and years ahead. Stay tuned for Chronicle 28!

Editor’s note: This article is the twenty-seventh of the BAREBOW! Chronicles, a series of shortened stories from accomplished hunter and author Dennis Dunn’s award-winning book, BAREBOW! An Archer’s Fair-Chase Taking of North America’s Big-Game 29. Dunn was the first to harvest each of the 29 traditionally recognized native North American big game species barebow: using only “a bow, a string, an arrow—no trigger, no peep sights, no pins—just fingers, guts, and instinct.” Each of the narratives will cover the (not always successful, but certainly educational and entertaining) pursuit of one of the 29 animals. One new adventure will be published every two weeks—join us on the hunt! You can learn more about the work and purchase a copy on Dunn’s site here. Read the twenty-sixth Chronicle here.

Top image courtesy Dennis Dunn